Curran to developers seeking funding: “Even if it is small-scale and anecdotal, you should have evidence of efficacy.”

There are research reports that highlight the efficacy of games as assessment tools, studies that show certain games can help students suffering from dyslexia and market analyses of the projected overseas learning games market. But how much of this research actually makes it into games you find in the App Store remains a mystery.

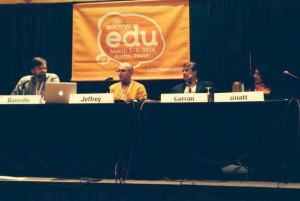

Representatives of three different sectors – game developers, investors and teachers – weighed in on the matter at a session Tuesday at SXSWedu and their answers raised as many questions as they likely answered.

The designer dilemma

Björn Jeffrey, the CEO of youth app powerhouse Toca Boca, stressed that one of the major problems is that “the bar is extremely low” to be considered an educational app in the App Store and so discerning between claims and actual educational value is impossible.

“There is no way to gauge if it is really educational,” he said, adding that many apps promote what he called “faux assessment.”

But the solution, Jeffrey said, is not as easy to identify.

He said he hoped a third party rating firm could offer parents, teachers and others a better sense to what products actually have some research and evidence behind them.

The danger, he said, is without more efforts to create a qualitative measure the battle for the trust of parents may be lost.

I spend a lot of time trying to convince people that using a learning app is better than just having your child run around outside… If a parent downloads a bad app that calls itself educational they may see no educational value in that device after that.

Björn Jeffrey, CEO Toca Boca

The investor’s questions

For those deciding whether to sink their money into a given educational technology, the question of research is often answered by the simple question: how much money is at risk?

Chris Curran, managing partner at Education Growth Advisors, stressed that private equity firms that are considering a major investment will scour thousands of pages of reports or conduct their own research, “to identify every possible risk or opportunity before they make the investment” of what could be tens of millions of dollars.

For Curran, the gaps in research exist more around the smaller-scale investments that are usually involved in learning games. He said that game developers who want to garner backing for startup projects should still come with some evidence.

“Even if it is small-scale and anecdotal, you should have evidence of efficacy,” Curran told the room of developers and researchers.

The teacher’s story

Developers and investors still need strong research to test concepts and prove efficacy, but for the teacher in the classroom the need lands closer to home, said Sujata Bhatt, creator of the Incubator School and a teacher.

“We need case studies of how using games really looks and really works that we can share with administrators,” she said.

She added that these case studies are critical because most change in larger school districts start from one teacher sharing what they are doing and what is working with another individual teacher. This one-to-one interaction is critical and thorough case studies of best practices strengthen those conversations.

In each case, the SXSWedu panel highlighted the need for research in different forms to continue to evolve game design, improve investment strategy and encourage innovation by teachers. Part of the challenge will continue to be finding what research is out there already and connecting those studies to the right audiences and then identifying gaps in the research and promoting more work in those areas.