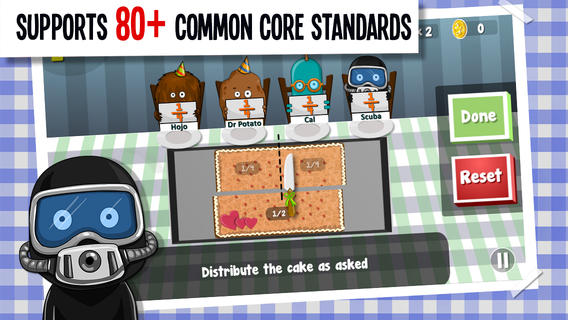

Math Planet hopes to sell in both schools and the consumer market, but its focus on Common Core standards speaks to its formal education bent.

The use of tablets in schools continues to grow and the differences between games for the classroom and games parents buy for kids continues to shrink, but still learning game developers need to clearly choose a primary market. They must decide — dive into the App Store fully or aim for adoption in the school market?

The choice should not be made lightly and fundamentally changes the game developer’s plans, from design through the business model.

Filament Games has decided to focus on schools, saying that decision was a bet on the long play.

“In the consumer world, within two weeks you will know whether you have a hit and within six months no one will remember the game. The educational world you may not know whether you have a hit for two years, but then you will have people buying that game for 10-15 years,” said CEO Lee Wilson, adding,

The consumer market is a hill of fast dollars and in the school market it is more a mountain of slow nickels.

Lee Wilson, CEO, Filament Games

Wilson stressed that he believed with the exception of Scholastic, no firms have truly succeeded in appealing to both markets, but some new players in the field hope to do just that.

Trip Hawkins knows the fast world of consumer games Wilson is talking about. Hawkins is a veteran of the video game wars, having started Electronic Arts and having developed Madden NFL and other top titles.

Now, Hawkins aims to use games to teach social and emotional intelligence and he wants a product that will work in both school and home.

“If…” has what could be one of the most creative business strategies we have come across in the last year of reporting.

It comes down to using Wilson’s fast hill of dollars to invest in what the company needs to climb the mountain of nickels.

“We initially make our debut on the consumer side so that we can then develop that market first and have customers fund our continuing R&D,” Hawkins said.

Game industry veteran Trip Hawkins hopes to use the quicker money from the consumer market to fund the school version of “If…”

“Certainly a school is going to have more functional requirements, for example they are going to want to have a more sophisticated teacher management system. They are going to want a lot more accounts per device, and they are probably going to want to have more explicit data about student choices that is available to the teacher,” he added. “So there is a more advanced feature set that we are going to have to work our way towards, but the other thing is we are going to want to be more confident about the learning measurements.”

But for every firm like “If…” there are as many like Pixowl, a savvy group of developers within the co.lab accelerator that explored the school market and decided not to take the plunge.

Pixowl co-founder and COO Sébastien Borget said the firm went into the accelerator intending to build a version of its world builder game The Sandbox for schools.

They started testing the game in a couple of Bay Area schools in California and were pleased with what they found, saying they “did not need the teacher [professional development] exercises to show them how the game would work in a lesson,” he said.

We had this game and we had this vision of having more teachers using it, but as it turns out I think this was a little bit too ambitious of a vision compared to the constraints of that market and all the preparations it requires in terms of documents, curriculum alignment, training, writing lesson plans and all that.

Pixowl co-founder and COO Sébastien Borget

But that didn’t fix the larger market problem.

“NewSchools Venture Fund was explaining the market is growing, but it is still a small part of the pie to be shared between a hundred or a thousand entrepreneurs and most of the millions of dollars being spent are going to a small number of companies like Pearson,” he said.

“So if you do your pure mathematics, you say, ‘Hmmm, I’m doing all that and at best, if I am the first app in the App Store I may make $100,000,’ but it is growing and it is sustainable revenue.”

The Temptation of Developer Parents

One of the trends driving the learning game industry is the growth of parental entrepreneurs. These are game developers who made commercial apps or console games, have kids and suddenly want to make things for their own children.

Marco Polo Ocean grew out of two parents who looked at the learning game space and saw an opportunity.

Marco Polo Ocean swam to the top of the App Store charts fueled by two entrepreneurs who wanted to create a compelling learning game for their own kids.

“As parents we didn’t want to just put Disney or Nickelodeon on the iPad like it is on the TV. Those apps are almost always very much about the characters from the movies and shows,” Justin Hsu, founder and CEO of MarcoPolo Learning, said. “We wanted the learning goals to be what came first.”

Or take the example of TurtleDiary.com, a startup that offers parents and teachers 1,000 online learning activities and at least 200 lesson plans. One of the founders, Neetu Saini, explained that, “Our vision is to create a program so schools and parents who do not have sufficient funds can make use of the tools required for a well-rounded education.”

These startups have been met with mixed success. Developers create a game or two, but sometimes struggle for sustainability.

What has sometimes been missing, according to some entrepreneurs and investors, is the underlying business plan to capitalize on quick success in the fickle App Store market or to survive the bureaucratic quagmire of school purchasing.

Another startup – EdShelf – emerged as a key trend story this summer — not by addressing this challenge, but by becoming a victim of it. The site allowed teachers to rank and review technology tools for the classroom providing an important tool for teachers seeking new ideas.

But as its founder told EdSurge, “The most important thing for an edtech company is to make sure you’re building a product that has a way to sustain itself. In our case, we were building a platform business that took too much time to find a revenue model.”

A social media campaign soon took off on Twitter, but the underlying economic challenge remained. There was no business plan to lead beyond they flurry of p.r. and that is the danger faced by many developers aimed at “doing good” without the financial plan to see it through.

The Case Against Schools

Still, there are companies out there successfully building games for the classroom. These firms have committed to building tools that will work in school and engage students. But that is not easy.

Developers in this space were quick to highlight some critical limitations they face in creating games for the formal education market.

First, there is the time. Game play in the classroom tends to be a short-term affair. PowerPlay, makers of the Math Planet games, found that time spent playing a game during a lesson tended to be between 10 and 15 minutes.

Over at iCivics, a suite of government and citizenship games that boasts more than 10 million game plays, Executive Director Louise Dubé stressed, “The whole industry of educational gaming still needs to capture more classroom time,” adding they are constantly working to be more than a supplemental activity in the classroom.

Then there is the business math of building a game for a single grade versus, what developers like Toca Boca and Pixowl have found, selling to the rest of the world.

Toca Boca CEO Björn Jeffery visibly shuddered when considering what it would take to make his app company work for schools.

Toca Boca chose to focus on the consumer market, not the school market. It just recently reached its 50 millionth download. Almost all of them paid.

“If we were to take on education and do it that way, partly we would lose all our international business. That’s number one. We sell in 160 countries and I am quarter Norwegian, a quarter Swedish and half English living in America. Trying to figure out the American educational system and realizing that even from state to state there are differences. It’s very complex,” he said.

If I were to try and do [learning game development for schools] by the book at a state level, it would require four or five or six times as much work and I would be cutting off 50 percent of my total market. I would be losing all the other countries because Saudi Arabia doesn’t teach the same way as Nevada does.

Björn Jeffery, CEO, Toca Boca

So let’s say you are willing to forego the global market and focus on schools, there are still challenges at the technology and user levels.

On the technology front, schools have radically different systems in place.

As Muzzy Lane’s Dave McCool explained, “In our view, we are making curriculum software for schools so the platform, the software structure, the compatibility and usability issues are every bit as big as the game design… You need to be web delivered. You need to integrate to web-based learning management systems and assessment.”

And even the mighty Google stressed the need to make technology completely fuss-free if it were going to work in class.

“If it becomes slightly cumbersome in a school, it becomes impossible. At Google we’ll all futz with our technology for a few minutes in a meeting to get something to work… We’ll take five minutes to make something work. We all live with it. Teachers won’t live with it,” Rick Borovoy, product lead for Google Play for Education, said.

Still, there is hope.

Recent reports have highlighted the need to expand the real-world lessons and applications of skills that games are often perfectly suited to the use of games and, according to experts, games continue to solidify themselves as a more core tool in education.

“The culture around digital games is growing to encompass a substantial proportion of the world’s population, with the age of the average gamer increasing every year. The gaming industry is producing a steady stream of games that continue to expand their nature and impact – they can be artistic, social, and collaborative, with many allowing massive numbers of people from all over the world to participate simultaneously,” The New Media Consortium’s 2014 K-12 Horizon Report concluded.

The Case for Schools

So why develop for schools? And once decided, how different is it then commercial work?

The why may be the easier question to answer.

“We very much believe that when you create a good piece of education technology and you make it available on the commercial market, the parents who can afford it are going to buy it. And the kids who come from families that have access to that kind of technology are going to benefit from it,” said Filament Games Chief Product Officer Dan White.

“In institutional education you have an opportunity to say we make this thing and it gets adopted – the caveat being it is really hard to get it adopted – if we succeed at that then all the kids will have access to it. It taps into the equity component of our mission.”

We want to have an impact and we don’t want that impact to be limited to the kids who come from a background of privilege and that is the beautiful thing about institutional education.

Filament Games Chief Product Officer Dan White

And that is something we have heard often. Game firms truly committed to going into schools aren’t in it for a quick profit or because their game is too nerdy to work outside the classroom. They are usually in it to change education and ensure access to technologies by all children.

Perhaps most telling of this need for a clear focus came when talking with Pixowl about why they decided they would go after the consumer market instead.

“If it’s not our DNA to do pure education and transform classrooms, then we were not doing it the right way. Some companies here [at co.lab] are not about gaming, they are really about transforming the classroom and they are really focused on how we do the curriculum matching and write those lessons,” Borget said. “The incubator is blending the two worlds and it enlarges your vision. It doesn’t turn you into an educational company if you don’t want to be one or did not intend to be one.”

If you are a company considering going after the school market, there are some tips we’ve heard from veterans.

-

Limit Yourself

First, the game needs to focus on the formal learning goals it aims to enforce.

“Games that we typically develop with [educational] partners start with the learning objectives first so we decide what the game design is going to be after we have listened to our partners and they have told us what the learning objectives are and we say “Ok, well then we need to do a role-playing game or we need to do a term-based game or a puzzle game” that will best achieve those learning objectives,” said Chris Parsons of Muzzy Lane Software, a firm that has worked with McGraw-Hill and National Geographic to build classroom games.

But more than just focusing in on learning objectives, it is embracing the vision of what the school wants to teach, said Hawkins at “If…”

“When you start to think about it being applied to learning and education, that’s where you have to take curriculum seriously and ask yourself ‘What is it governments believe is important in education?” Because if you are not lined up to do what governments believe in, you are probably not going to get very far as far as what is it you care about teaching and having people learn,” he said, adding, “Obviously, we’re harnessing ourselves to these constraints about what does the government say is important, what does the science say is important, what does the domain analysis say, what does the teaching standards require and we’re making the game development team conform to that instead of making their own Tetris.”

-

Embrace the Chaos

But developers caution you cannot go on standards and learning outcomes alone. You must consider the teacher and work with them to ensure the game will actually fit into classroom schedules and technologies.

This part of the process can also feel like a limitation, but the minds behind Motion Math beg to differ, saying it is where the actual creativity kicks in.

“We talk to teachers and look at data on what Common Core concepts kids most struggle with – what are the biggest pain points we can turn into something delightful?” Then we talk to teachers more and look at resources already out there, we look at learning literature on what experts know about how kids learn that concept, to get a sense of what’s already known. And then we start brainstorming what kind of game mechanics might teach it,” explained Jacob Klein.

“Sometimes that’s thinking more and more about the concept, or getting inspired by a non-learning game that has a fun dynamic, and that’s a very open, chaotic part of the process.”

And this creative process, developers told us, is critical to the game being an actual game and not a series of flashcards or an online quiz.

Jeffery over at Toca Boca said this is his main criticism of many learning games – they are so focused on the learning that they forget the game. When this happens, Jeffery said, the entire point of the game is lost, saying, “If there is no engagement and there is no usage than there is no educating anyway and that, I think, a lot of people here miss. They are so focused on the game being super correct from an educational standards that you almost forget about the kids.”

-

Don’t Build a Game

Finally, people we spoke with have stressed the idea that a single game will not cover all the skills it needs to cover or produce sustainable revenue.

New Schools Venture Fund has backed many edtech startups and Shauntel Polson said they look for game developers to come with a full business plan for a series of games.

“You can’t just make one game – especially if you are trying to do something in the classroom – you have to think about the suite of games that are going to cover a specific topic or a specific curriculum area,” she said.