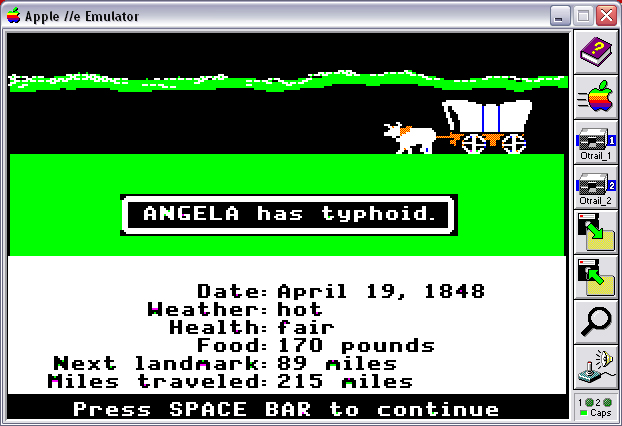

A computer game invented by Minnesota history a teacher in the late 1970s might seem like a bore these days, with its lo-fi graphics and lack of interactivity.

The Oregon Trail remains a common denominator for American students born in that generation. It has its own meme. BuzzFeed publishes cheeky lists dedicated to it — repeatedly. Adults don costumes and reenact the game.

Which education game will serve as a touchstone for today’s students? Their games are far flashier than that pioneering classic. Advances in technology, and an influx of computers and other devices in schools, have ushered more choices for parents, educators and students.

A national survey of teachers, released Oct. 20, suggests a majority of K-8 teachers believe that educational games are valuable classroom tools, but few say they know where to find trusted resources to ensure the games they use are effective and backed by research.

A national survey of teachers, released Oct. 20, suggests a majority of K-8 teachers believe that educational games are valuable classroom tools, but few say they know where to find trusted resources to ensure the games they use are effective and backed by research.

“They don’t know where they can go or who they can ask,” said Lori M. Takeuchi, co-author, with Sarah Vaala, of the report on the survey’s findings.

The survey of about 700 teachers found that three-quarters of teachers said they used games in the classroom, according to “Level Up Learning: A National Survey on Teaching with Digital Games,” which was produced by the Games and Learning Publishing Council at the Joan Ganz Cooney Center. And the majority said they believed games were effective for teaching and learning.

“What did surprise me is the ubiquity of digital games,” said Michael H. Levine, the founding director of the Joan Ganz Cooney Center, an educational media research nonprofit in New York City. “I believe these data help to make the case that the shift from print to digital is happening in many classrooms, and digital games are one blended learning opportunity that is happening.”

Related: What happens when a robotics class starts the year with no robots?

The Apple store and the Android marketplace offer a smorgasbord of choices for teachers. And web-based games are often available for free. Some are educational. Others? It’s hard to say. In some cases, label “educational” appears to be used as a synonym for “children,” and there’s little evidence that the way students learn was considered in the development.

The majority of teachers surveyed said they use games to teach lessons, not just for a recess-like diversion on the classroom. More than 40 percent of teachers who use games in the classroom reported they used them for lessons aligned with state or local standards. Eight out of 10 teachers said they want it to be easier to find games that are linked to the curriculum, and the majority reported there were not enough high-quality choices.

The majority of teachers surveyed said they use games to teach lessons, not just for a recess-like diversion on the classroom. More than 40 percent of teachers who use games in the classroom reported they used them for lessons aligned with state or local standards. Eight out of 10 teachers said they want it to be easier to find games that are linked to the curriculum, and the majority reported there were not enough high-quality choices.

Teaching with research-backed games does not have to mean trading in the fun stuff for glorified electronic workbooks. Evidence exists that the so-called “chocolate-covered broccoli” approach to educational game development is not as effective as one that makes games engaging, according to research cited in the report.

There are resources available for evaluating the quality of these games, but few teachers were aware of them, according to the report. For example, Common Sense Media, a children’s advocacy group in San Francisco that rates all types of media, has a site called Graphite that offers reviews of digital games that could help educators navigate an increasingly crowded, and rapidly changing, marketplace.

Still, said Levine, “We absolutely need more research into what is going on with these games.”

The survey of K-8 teachers showed the perceptions of teachers. It did not analyze test scores or other metrics that might be seen as evidence of educational effectiveness.

The report’s authors suggest building a common set of terms and labels that teachers can use to assess games, and creating a framework for integrating them into classrooms beyond drill-and-practice. They also argue for more professional development and more research on the topic.

Among the other findings is a suggestion that the old Oregon Trail, a long-form game, might not be so popular these days. Teachers reported that they were more likely to use games that were quick hits. And the epic adventures played out in early versions of the pioneering educational game offered far less interactive learning, real-time data for teachers and pizazz than what is found in the classrooms of this generation of students.

But that could change.

“This is one snapshot in time; these issues are clearly moving,” Levine said. “There are all these different ripples. I think teachers are a little unsettled by these ripples.”

Editor’s Note: This piece originally ran at The Hechinger Report, an independent news operation covering education and is funded by the Teachers College at Columbia University.