Hellgate Elementary in Missoula, MT should be the ideal environment for new and innovative learning games to thrive. So why is a school with ample bandwidth and 800 iPads still using only a handful of games, many of which were released in the 1990s?

Educators at Hellgate, a Blue Ribbon School District that is seen as a statewide model for edtech, have used programs that incorporate gaming elements for years, but they have yet to find a game or game system that fully meets their academic and logistical needs.

“It’s a very fine line,” said Mike Straw, a fourth grade teacher. “We want them to have fun and be engaged, but we also need that productivity part of it.”

And productivity is one of the central things Straw looks for when choosing how to use technology. Straw looks for programs that are not only engaging but also academically rigorous while providing streamlined communication regarding feedback and assessment.

It’s a combination that, so far, he has been unable to find in a single program. Teachers at Hellgate report keeping an eye on teacher networks and the administration say they will get the off pitch from a salesperson, but much of what we found echoes what the Joan Ganz Cooney Center reported last year – teachers learn about games from other teachers.

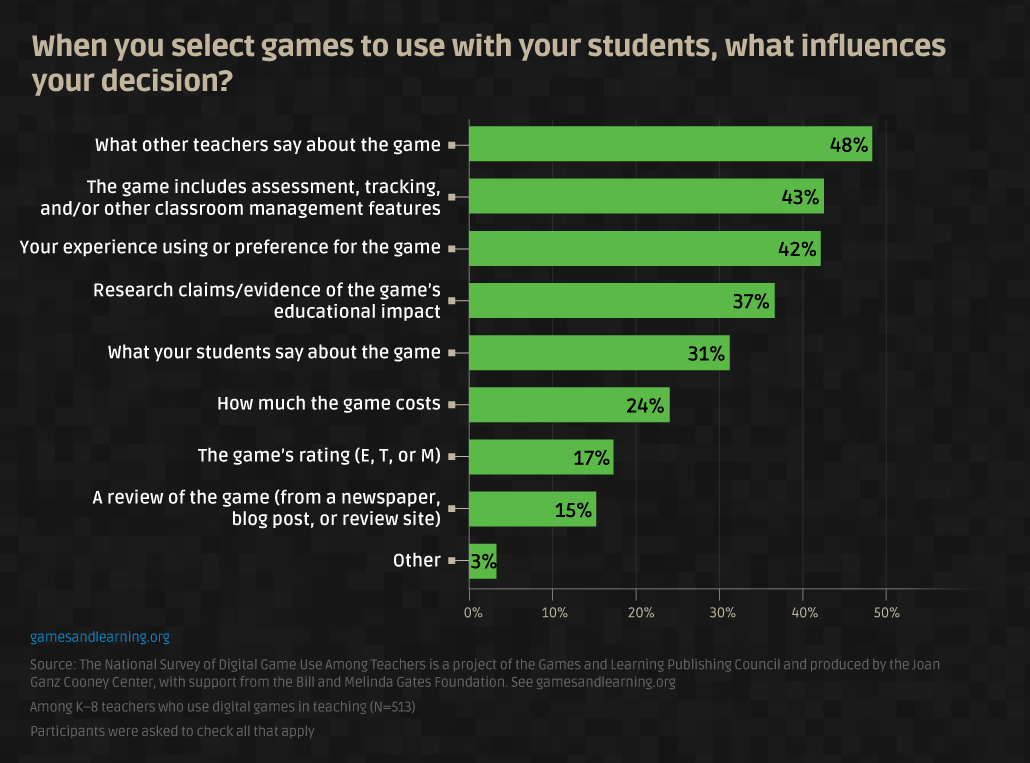

That survey found that anecdotal feedback continues to be a powerful driver of how teachers choose games. Between recommendations from teachers (48%), their own experience with the game (41%) and feedback from students (31%), many of the things that influence teachers’ selections amount to word of mouth.

Hellgate math specialist Russ Parrish agrees that finding the right mix is difficult.

Parrish knows why he wants to use games in classing, saying, “Rather than rote memorization and repetition, it becomes fun for them; it becomes challenging for them.”

He does deploy some games. He has students compete against themselves to improve their scores, which in turn develops an intrinsic drive to improve classroom skills. Programs such as Front Row, KnowledgeWorks and Micrograms incorporate gaming elements into their interface, while covering all Common Core strands thoroughly and effectively, Parrish said.

The combination of engagement with clear academic rigor is one secret to their longevity in his classroom – Parrish has used both KnowledgeWorks and Micrograms since he began teaching 16 years ago, with clear results: “We had kids who I was told would never be above the fifth percentile who were well above the seventieth percentile on the national tests. I think that speaks for itself.”

It’s a very different model than the fickle world of the App Store or Google Play where the 15 minutes of celebrity rule rules.

But it is also a world that requires more from a game. For example, both Parrish and Straw cite the difficulty of finding a game that helps both remedial and advanced skills. “Sometimes, I have 8th graders who might score in diagnostics at a third grade-level and… I need to have the availability to be in the third grade programming to move them up,” Parrish said. He believes that, with the help of supplemental gaming technology, students at an eighth-grade level of maturity can progress as far as two grade levels within a quarter.

It’s tough to find a game that can scale that much, especially as game developers race to create games that reflect Common Core standards. Parrish said he’s seen self-adjusting games often become all but worthless at the far ends of the achievement spectrum.

So what could unlock more games in Hellgate’s classrooms?

In addition to the flexibility of standards-based academic rigor, Straw emphasized that a truly successful learning game would need to streamline communication between the teacher, parents and administrators.

“You don’t want to have a paper trail. You want to seamlessly share this information,” Straw said, adding clear and simple communication to teachers, parents and administrators would appeal to many educators.

Parrish and Straw agree that the ideal learning game would be a delicate mix, combining a program that felt like a game for students, demonstrated a high level of academic quality and communicated with all interested parties.

“When we are looking at apps and websites, our primary focus is ‘what am I going to enhance with this, and how do I get feedback and assessment using this piece?’” Straw said.

In an already decorated district, a learning game at the intersection between student engagement, curricular rigor and communicative assessment would prove a welcome educational tool.

“The easier you can make this on the school,” Straw said, “the more clients you would get.”