The idea for her new book, SuperBetter: A Revolutionary Approach to Getting Stronger, Happier, Braver and More Resilient – Powered by the Science of Games, came to game designer Jane McGonigal in some of her darkest days.

Having suffered a severe concussion, she was unable to go about her daily routine and lead a normal life even after thirty days; McGonigal started having suicidal thoughts – a common symptom of postconscussion syndrome. Realizing the severity of her situation, McGonigal told herself that:

I am either going to kill myself, or I’m going to turn this into a game.

By turning her recovery process into a game, McGonigal said she started feeling better within weeks. She shared her method on her blog and since then more than 400,000 people have played the online version of SuperBetter.

The process of gamification has helped people overcome challenges related not just to mental health but other personal struggles as well. The data collected from these 400,000 players was analyzed and tested. What the data found, McConigal says, is that “that gameful ways of thinking and acting are a skill set that, once learned, you are likely to keep practicing and benefiting from.”

Games as Science and Art

The book is the result of five years of research on McGonigal’s SuperBetter method. After seeing the results of her method first-hand and hearing from others who came across her blog, McGonigal wanted to put the power of gaming to the test.

“Even though game design is an art form, it’s also a science – and I think we spend a lot of time in the past decade thinking about how games are an art and now we need to think about the science as well,” she recently told gamesandlearning.org.

McGonigal collaborated with the University of Pennsylvania as well as Ohio State University to conduct two separate independent studies on the SuperBetter approach.

The University of Pennsylvania study was a randomized controlled study of the SuperBetter method and its effects on depression. The Ohio State University study was a clinical trial funded by the National Institutes of Health.

The research started McGonigal thinking about all the ways game designers could improve their products and how player could use games to help themselves if they just unlocked the research. In her book, McGonigal emphasizes how “games are not just a source of entertainment. They are a model for how to become the best version of ourselves.”

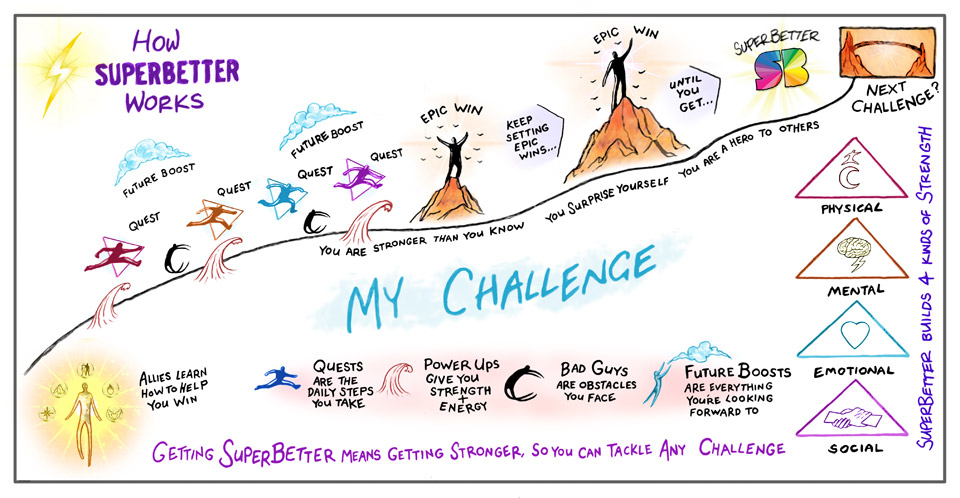

It’s a theme she re-emphasized in talking with us, saying that because she saw that games were effectively addressing the needs of mental health she wanted to delve into the research a bit more. Her goal she said, was to make it so that “game developers could start to really use that research to make games that have a positive impact on people and so that people who play games have a better sense of what games they can play to build up different kinds of resilience in their own lives: physical, mental, emotional and social.”

Over the past decade, McGonigal said there have been a lot changes in the way people think about, play, and design games. According to McGonigal, more than 1.23 billion people play video games for at least one hour a day.

Realizing how big the game playing community is, McGonigal said, is “really helping us have conversations about what we’re playing and why we’re playing.”

The maker movement has also had an impact on games, she added, not just around the fact that playing games is good for you but that “learning to think systematically, like a game designer, learning to have that confidence with technology, to feel that you are a creator, that you have these skills whether it’s programming or design or architecture – I think that’s maybe one of the most important, maybe a little underrated developments too.”

One of the things that surprised McGonigal while doing her research for the book, she says, is that the number one predictor of gamers who go on to be game addicts vs. gamers who make reap the benefits from games are those gamers who see games as an escape from real life vs. those who play to make their life better. This idea of “playing with purpose” is a crucial component in seeing games as a way to build positive real life skills such as problem solving, especially in kids.

The worst thing you can do as a teacher or parent is to say to a kid ‘stop wasting your time with that game’ or ‘put that away and go do something real’ because what you’re doing is reinforcing the idea in the mind of that player is that there is no connection to reality. And that turns out to be the number one predictor of addiction because they start to view games as a way to block out their problems; they use it as a crutch.

— Jane McGonigal

The alternative, she added, it not that hard, saying the best way “to help kids really benefit from games and really unlock their power is to just start having conversations with them, talking to them about how the games are building up real strengths. There are questions every parent or educator can ask a kid: what does it take to be good at this game? What makes this game hard? What do you have to be good at to meet that challenge?”

If a child has been working on a level for four hours or four days to say “wow – you’ve really been working on this for a long time – you’re a real determined person, aren’t you?” She said that conversations like this are the number one thing parents and educators can do to help kids see games as skill builders not time wasters”

And this, she said, is one of the main reasons why she wrote SuperBetter – because she wants “every gamer, every parent of a gamer or a teacher of gamer to be able to say you haven’t thought about all these skills and abilities you’re building? Let me tell you about some of them.”