Ten years ago indie game developer and author Sande Chen studied the state of the games for impact movement in the book she co-authored called “Serious Games: Games That Educate, Train and Inform.” We’ve asked her to revisit that work to see what has or has not changed in the field of learning games.

INTRODUCTION: BACK TO THE FUTURE

It seems like it’s never been a better time to be a educational game developer. 10 years ago, when David Michael and I conducted a serious game developer survey, there wasn’t so much buzz around educational games and technology. According to Ambient Insights, global revenues of all game-based and simulation-based learning products topped $5.7 billion in 2014 alone and are projected to grow to $13.2 billion by 2019. Educational technology investments have leaped into the millions and billions and the Department of Education (ED) has been out to meet with educational game developers while promoting its newly released Ed Tech Developer’s Guide. Half of the ED’s Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) portfolio now consists of educational games, a clear indication of how far the industry has grown.

A decade ago the picture was very different. Of the various markets covered in our book, Serious Games: Games That Educate, Train and Inform, educational games seemed to be the least lucrative, as compared to military, government. health, or corporate sectors. Ultimately, we concluded that the future of educational games in the classroom would depend greatly on teachers and school administrators.

AUDIO: CONVERSATION WITH SANDE

Educational games are now in the classroom and likely to remain, but adoption rates have been slower than serious game proponents had hoped. Despite a great deal of academic research on how games improve learning outcomes, teachers don’t tend to use the more effective immersive games, preferring bite-sized nuggets of interactivity. Games also drop off in usage after middle school, reflecting less time for exploration in high school. The structure of formal education hasn’t changed much to accommodate the use of educational games.

But what about all those rosy numbers? If developers haven’t hit the jackpot with selling to schools, who are they selling to? Is it consumers, corporations, or the old stand-by, the military and government agencies? While we had separated these out into discrete markets for the book, many people do not, regarding any aspect of training to be education. In the consumer space in particular, the revenue numbers for game-based learning are more reflective of early development tools, language-learning programs, and brain trainers like Lumosity than educational games intended for the classroom.

NewSchools Seed Fund’s analysis of their 2013 venture capital investments in formal and informal preK-12th grade education indicates that only 4 of the 115 ventures, approximately $40 million out of $452 million, were in the gaming category, and primarily focused on younger learners.

As EdSurge notes the numbers can be misleading because educational technology could also mean backend administrative software or even a photo sharing app. They’re not necessarily games. The excitement in edtech revolves around game-based learning as well as applications that deal with classroom management, online education, and communication between teachers, students, and parents.

Once you drill it down to educational games that teach students in schools and elsewhere, has the situation improved for educational game developers?

In an attempt to find out, I created an online survey with many of the same questions as the original survey from 10 years ago and interviewed 22 developers in the educational game space. The survey ran for 2 weeks in August 2015 and got 70 responses from a cross section of the industry: game developers, academics, consultants, and educators. Roughly half of the respondents had a background in entertainment games and the other half from education. The majority had 3+ years of experience in educational games and had been involved in the production of 1-5 games. The games, mostly about STEM topics, targeted an assortment of platforms for a variety of age groups. While qualitative in nature, I believe these combined results are sufficient enough to create a snapshot of what’s happening with educational game developers in 2015.

Thinking Big

To succeed in educational games, a developer needs to think big. As David Langendoen, co-founder of Electric Funstuff, says, “To get a reliable ROI (return on investment) and figure out a business model, you need to think ‘Who is going to buy 10,000 copies of this thing?'” For entertainment game companies, that’s the general public. For educational game companies, it’s often schools. There are 54 million K-12 students enrolled in public and private schools across the U.S. However, selling to schools is a slow and difficult process, so if not schools, then who?

There’s parents, who prefer free apps but are willing to shell out dollars for an electronic babysitter with educational value. Games for the PreK set are consistently among the top grossing educational apps in the Apple iTunes app store. According to Common Sense Media, in 2013, 58% of American parents reported that they had downloaded apps for their children. The market dries up as children age because by around age 8 or so, as children want to make their own purchasing decisions and they generally prefer entertainment-oriented titles. According to one NYU study, 80% of children would play an action game, but call it an educational game and the number drops to 20%.

Alternatively, a company could tap into more lucrative training markets for multiple revenue streams. Virtual Heroes, whose clients range from the CIA to Genentech, has developed games, simulations, and virtual worlds for government agencies, the military, corporations, non-profits, and museums as well as schools. It could even be considered edtech since it offers licenses for its training and education platform, Go.

I realized that the more money that is on the table, the more risk-adverse the decision makers become. They go with safe choices that if it doesn’t work out, who can blame them.

— Former teacher Peter Shea

Do Schools Have the Money?

The public perception is that schools have no money. They can’t afford to pay for games or hardware, let alone fund game development. “The biggest problem I’ve found with the educational market is that your biggest market is the public school system and the public school system has zero money,” says Judy Tyrer, founder of 3 Turn Productions. Extrapolate that sentiment further and the mantra becomes that teachers have no money, colleges have no money, museums have no money, after-school programs have no money, and any other struggling non-profit you can think of has no money. Kellian Adams of Green Door Labs, who typically works with the education department at museums, says, “If a non-profit has zero budget, then the education department of a non-profit has the zero-ist of a zero budget.” Slate Science, makers of the educational game platform Matific, has even helped schools find grants that would allow the schools to purchase their products.

As a result, some developers rely on crowdfunding, corporate sponsorship, or grants so that their products may be available to schools for free or at a dramatically reduceed cost. Others run pilot programs, allowing schools to benefit for free while the companies collect data on the game’s use in the classroom. Still others bank on gaining exposure and users with hopes that the endeavor will translate into future sales in the consumer space. They might create a free Edu version for schools while promoting the feature complete version for purchase. The free-to-play business model, common in mobile games, generally does not work well with teachers, who balk at flashing ads or in-game purchases.

VIDEO: SpaceChem Trailer

“We actually give away SpaceChem for free to schools,” says indie developer Zach Barth in an April 2015 interview on Gamasutra. “At one point, I thought we were going to sell it, and offer a bulk discount, but the only bulk discount that works is free.”

But if schools really had zero budgets then textbook publishers would be out of business. For FY2013, the New York City school system alone spent $101 million on textbooks. Schools have different budgets, whether for specific subject areas, technology, curriculum or supplemental, or “intervention” products to help struggling students. In some budgetary buckets, schools may have more than adequate amounts of money while other buckets are almost always near-empty. That’s why anecdotes exist of schools who have more interactive whiteboards than they know what to do with while at the same time pushing developers to make games free because of lack of funding.

Former teacher Peter Shea, now director of Professional Development at Middlesex Community College in Massachusetts, recalls a time when several million dollars were available through a grant to help workforce education. An advocate of simulation-based training, he was excited about the possibility of seeing those millions fund game development. Instead, the money went to digitize lesson plans. “I realized that the more money that is on the table, the more risk-adverse the decision makers become,” he says. “They go with safe choices that if it doesn’t work out, who can blame them. Who doesn’t like digitized lesson plans?”

The Free Flood

The flood of freely available educational materials, not only from educational game developers but also from open educational resources (OER), is precisely why it’s hard for an administrator to stand up in a budget meeting and say, “We spent $100,000 on a game!” Teachers have come to expect that educational materials, even digital games, are free or at the most, cost no more than a cheap app in the App Store. Even home schoolers who aren’t subject to a school board and could pay for consumer copies have contacted educational game developers trying to get games for free. There seems to exist a serious disconnect between costs, value, and what is a quality product.

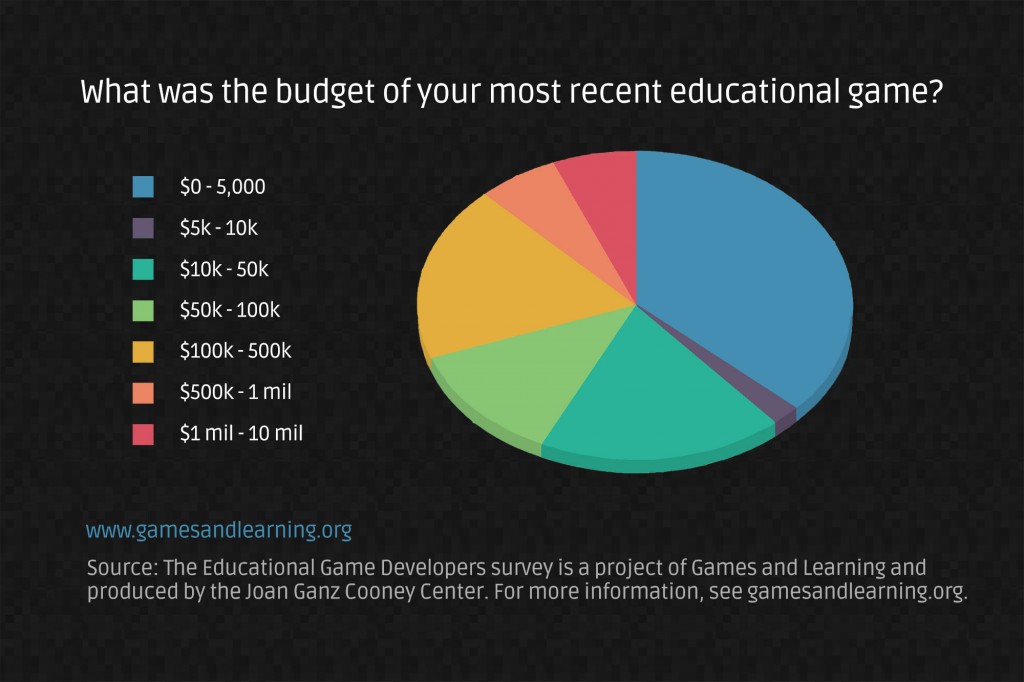

In New York City, a digital game budget of $10,000 is not inconceivable and may even be on the low end, but to a school administrator, this may sound mind-boggling. Langendoen, who has been in the educational game industry for 17 years, says, “The challenge that all of us developers are facing is that as the quality requirements of the games increase… production costs, design costs, all of that could be relatively high and the market has trouble valuing it.” A custom designed educational game that has custom programming and custom art is no easy task.

In New York City, a digital game budget of $10,000 is not inconceivable and may even be on the low end, but to a school administrator, this may sound mind-boggling. Langendoen, who has been in the educational game industry for 17 years, says, “The challenge that all of us developers are facing is that as the quality requirements of the games increase… production costs, design costs, all of that could be relatively high and the market has trouble valuing it.” A custom designed educational game that has custom programming and custom art is no easy task.

Moreover, the sheer volume of free stuff makes it difficult for any specific developer to be discovered and for teachers wading through it all to determine which games are good and actually educational. Given that teachers have limited free time to do full-scale searches, the onus is on game developers to cut through the noise and promote their products to teachers. For small developers, especially ones without a sales force, this may be a challenge since they may not be knowledgeable enough about marketing to do it successfully on their own.

Regretfully, says Langendoen, “There is some really good work out there from a number of developers and it just gets lost due to the nature of the marketplace.”

As for the quality of educational game design, it’s unknown if administrators can recognize a game’s value or if they are simply looking for chocolate-covered broccoli or assessment engines. To prove quality, some developers find it important to have research studies done on their products or to get stamps of approval. However, research studies listed on a Web page, wonderful reviews, and all the awards in the world doesn’t always translate into sales, especially when so many game developers feel compelled to offer their game at deeply reduced cost or even free.

“We get lots of people downloading our app, but they’re downloading the free version of it, so that doesn’t help the company,” says Karen Littman, founder of Morphonix.

In general, the developers interviewed who offer their products for free have not faced much resistance to placing their products in classrooms. Many interviewees in this position mentioned plans to monetize in the future. As indicated by the survey, the #1 issue that respondents felt needed to be addressed to improve the state of educational game development was lack of acceptance by schools. Beyond cost of the products, there may be other reasons for this reluctance.

It’s an App, an Interactive, a Simulation, and is it a Game?

Research has indicated that for some schools “game” is still a four-letter word. According to some teachers, administrators will buy anything that’s called an “app” or an “interactive,” but they’re very hesitant to buy a “game.” Somehow, the word “app” doesn’t have the same connotation as a frivolous “game” and maybe it’s a more accurate categorization in defining the platform.

Even within the educational game community, there is a struggle to find the right label. Educational software and edtech are broader categories that again, include games but are not necessarily games. Edugames, game-based learning, and learning games seem more on track while gamification, perhaps not. Maybe all this semantic distancing is a response to the cringe-worthy games of the 1980’s known as edutainment. Lumping games of varying quality and varying forms together as one has led to confused expectations. Educational game developers may need to be flexible when dealing with administrators who can’t justify spending money on a “game” but don’t mind a “simulation.”

“So much of how we learn is play but I think there’s this circuit breaker in some educators’ minds that if you introduce the idea of fun, you might be perverting the efficacy of the instruction, which is total nonsense.” says Conall Ryan, CEO of Muzzy Lane Software. “If you remove the term and deliver it, they love it because the students are so much more engaged.”

But why is this word, “game,” so disliked? Unlike years ago, there are more studies than ever on the effectiveness of video games on improving learning outcomes. Still, a majority of survey respondents indicated that more research on the effectiveness of games is needed, signaling that perhaps existing research papers are not well-known.

In March 2014, SRI Education conducted a systematic review of research literature on simulation-based learning for STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) subjects in K-12 classrooms. Of the 59 research studies and 260 papers, simulation-based learning was shown to be more effective than non-simulation-based learning, especially in science. Similarly, in “Digital Games, Design, and Learning: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” also from March 2014, the researchers concluded that game-based learning was generally more effective than non-game instruction.

It’s true that there has been more acceptance of educational games in classrooms, compared to years past, and in grades K-8, teachers may routinely use games. Middle school seems to be a sweet spot for games as middle school teachers often have more flexibility than high school counterparts. At higher grades and at the university level, with the exception of business and medical simulations, games are seen less often as teaching tools.

Many survey respondents were optimistic about personalized, adaptive tools that promote critical thinking. However, several felt that the education establishment is not prepared to accept games fully into the classroom. One respondent wrote, “Although individual teachers may achieve it in their own classrooms, ultimately there is too much money and power invested in keeping the American educational system the way it currently is.”

Data and Support

STAT: Developer Survey

Data.

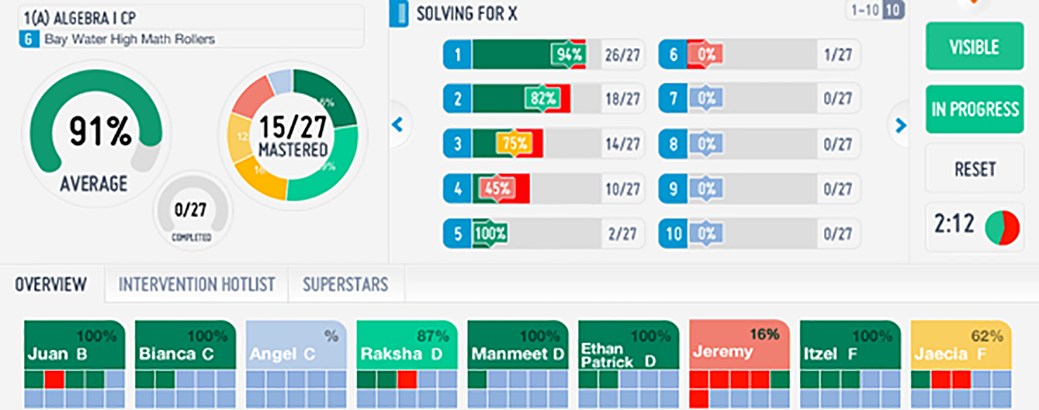

That’s #1 on most administrators’ wish lists. A school’s performance is measured by how well the students do on standardized tests. Administrators and teachers’ jobs hang on these numbers. Fortunately, this is an area where game developers can help and in a big way since they have been using data analytics to observe user behavior and improve their own products for years. Learner analytics has the potential to radically change the way we teach.

For example, with just one hour of continual play each day, Slate Science’s Matific can track which students are doing well and which students are falling behind standard levels. Not only can the teacher intervene immediately instead of waiting 3 months for the information from standardized test results, the teacher can personalize the instruction by focusing on problem areas, all without embarrassing struggling students.

Assessment and data tracking differ from company to company according to needs. Muzzy Lane Software, a company known for simulations, records decision-making points so that both teacher and student can review what the student did and where things may have gone wrong. London-based Kuato Studios at first tried existing mobile user analytics solutions like Swrve but frustratingly found that it wasn’t a good fit for mapping learning outcomes. Like many other companies, Kuato Studios eventually developed its own system to accommodate both gaming and educational purposes.

There is no standard platform for learner analytics.

In the past, just finishing the game or teacher observation might indicate the student had mastered the material, but these days, clients demand more. They want to know if the game is aligned with Common Core standards and they want the data on every learning objective. Even if the game fits Common Core standards and has levels corresponding to demonstrated skills, administrators want to know more than how many levels the student completed. Traditional gaming feedback mechanisms like points and levels don’t tell administrators what they want to know, or at least not in the way they want.

Individual states may have their own standards too, in addition to child privacy laws, as Amplify learned when it had to comb through its games deleting any mentions of consumer brand names in order to sell to California. Furthermore, a game can match all of these standards and still be a tough sell if the game’s topic is not generally covered in formal curriculum. Schools typically spend the bulk of their curriculum budget on English language arts (ELA) and mathematics, areas crucial to basic competency.

If a game isn’t aligned with Common Core, then it can only be considered supplemental material, and not curriculum.

By its nature, supplemental material is supposed to be used in conjunction with textbooks, to enhance understanding and not replace curriculum. In practice, the usage difference between supplemental and curriculum can be superficial and schools now spend twice as much on supplemental materials than on core curriculum products. However, it’s still important to fit the standards even as supplemental. Matific covers math curriculum, but it is marketed as supplemental because there’s a faster process to get supplemental materials into schools.

Once the game is in the schools, teachers are the next possible obstacle. As anyone who has tried to implement technology across an organization can attest, just because the technology is available doesn’t mean that people will use it, especially if they don’t know how to use it. This means that the game developer needs to provide training, or professional development, on how to use analytics, or at the least, teacher support in the form of sample lesson plans.

Scott Lamb, Technical Director of Kuato Studios, says, “If it doesn’t mesh with the teacher’s normal daily routine sufficiently and if you don’t provide the lesson plan and you don’t provide some support, then you’ve effectively said, ‘Use our thing, but to do that, you’ll have to do a whole bunch of homework yourself just to work out how to build it into your lesson.'”

Given the choice between not using and using something they don’t understand, teachers tend to avoid the hassle. It’s already a hassle handing out devices, making sure they’re all charged up, helping students with logins, checking to see if the Internet is working, and collecting the devices back again. Moreover, the product needs to be platform agnostic, able to work on the school’s existing technology, whether it’s tablets, Chromebooks, or old PCs.

“The schools’ ability to adopt game-based learning is contingent upon the device offerings that they have,” explains Brandon Pittser, Marketing Director at Filament Games. Basically, if schools can’t run the game with what they have, then they probably won’t want the game.

For a developer, these requirements add scope to a project, which in turn increases the budget. Teacher editions and professional development may indeed be good revenue streams and fortunately, there’s a separate budget for professional development. To be certain, it’s necessary to support the game, and lesson plans are a great idea but all these added tasks do pile up. Because schools want these features, it’s become necessary for developers to comply.

“You have to build the center that makes sense for tomorrow, not just today, which can be confusing to administrators who aren’t tracking games or social media,” cautions Kurt Squire, Romnes Professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and Co-Director of the Games+Learning+Society Center, “If you aren’t careful, you can build a program that meets the needs of 2001 instead of 2021.”

By comparison, the path to success with an indie entertainment game seems to have less headaches. Charlotte Ellett, co-founder of indie game developer C63 Industries, says, “Entertainment seems like a more accessible market: You put your game out there on a digital platform such as Steam and you go to events to market it. I would like to work with the education market but I don’t know how to approach it.”

Just setting up a website with an offering, that’s effectively equivalent to staking a flag in the middle of the desert. It doesn’t necessarily mean that people are going to find you.

— Brandon Pittser, Marketing Director at Filament Games

The Waiting Game

For educational games, there are no easy distribution routes into American primary and secondary schools. Yes, there’s Google Play, iTunes, and Steam to maybe get some notice, but it’s not as easy as Australia’s National Digital Learning Resources Network, an online portal of approved, curriculum-ready digital resources that teachers can easily download and use in classrooms. Instead, an educational game developer in the U.S. has to do it the old-fashioned way: school by school, and district by district. One can also sell to states, but the approval process is much longer. For California, Florida, and Texas, that means more than 6 years, at least for curriculum.

By contrast, for a small school district, it can take 18 months from initial contact to final sale. Large school districts, the ones with more money, can take longer due to formal purchasing procedures that require multiple rounds of approval. For K-12, it might be a matter of a 2-3 years. Pittser says, “Adoption can take place over the course of several years. It requires a great deal of patience and a great deal of persistence.”

On the school level, it isn’t as bad, but a developer would still need to convince school administrators and address all of the concerns previously stated above. Also, keep in mind that a school’s fiscal year is June 30 – July 1. There are specific times for RFPs (Request For Proposal) and if a developer misses that window, well, there’s always next year.

For developers without a dedicated sales force, there are freelance educational sales for hire, but after commissions and expenses, this may turn out to be cost-prohibitive. Plus, there’s no guarantee the educational sales agent knows anything about selling games. Doing it alone means going to conventions and talking to teachers, principals, superintendents, administrators, library media specialists, curriculum specialists, curriculum directors, basically anyone who can help pave the way to adoption. Essentially, the company needs to start building a professional network.

“There’s no replacement for direct interaction with a customer,” says Pittser. “Just setting up a website with an offering, that’s effectively equivalent to staking a flag in the middle of the desert. It doesn’t necessarily mean that people are going to find you.”

VIDEO: Inanimate Alice

Teachers are often instrumental in introducing and championing a game to school administrators. Will Penner finds that the best sales approach for him is to gather up a bunch of math teachers and administrators to play his game, Mathopoly. During the game session, he explains how teachers can use his game in the classroom.

Pittser encourages developers to look at international markets as well because despite differing standards, there might be schools who are interested even if the games are in American English and aligned to American standards. Matific is sold worldwide and Guy Vardi, CEO of Slate Science, says that each country has unique market characteristics. In some countries, Matific is sold to private school networks and in others, there is a bidding process. Most of the time, localization will be required, especially for those games focused on English language arts. Inanimate Alice, a transmedia story that will evolve into a full-fledged 3D game by the last episode, has versions in Spanish, French, Italian, German, Indonesian, and Japanese.

Vardi does feel that the educational market sector has potential but reiterates, “Most importantly, you need to be extremely patient. It’s just a really long process.”

Conclusion

Despite more support for educational games from the government, the general public, and teachers, there has not been much progress over the last decade. Educational games, no matter what you call them, have never really recovered from the public perception shaped by a rash of poorly designed and deeply discounted edutainment products. Consumers continually devalue educational games, expecting them to be free or low cost, with little understanding of quality differences. This mismatch between costs and value has led to unreasonable expectations.

“I’m concerned about the idea that you can deliver education for $2.99,” says Ian Harper, producer of Inanimate Alice.

Hope lies with the rise of “digital natives,” those generations that grew up playing video games, and with the possibility of better distribution networks over the Internet. Still, the promise of better technology has led administrators to zero in on how technology can improve assessment tracking. While it’s apparent that learner analytics will become a standard part of educational games, it’s important that the industry does not lose focus on what’s important, the learning experience.

There are positive notes, however, and the next few articles will discuss changes in funding sources, the lessening clash between games and education, and informal learning spaces.

Sande Chen is the co-author of Serious Games: Games That Educate, Train, and Inform. As a serious games consultant, she helps companies harness the power of video games for non-entertainment purposes. Her career as a writer, producer, and game designer has spanned over 10 years in the game industry. Her game credits include 1999 Independent Games Festival winner Terminus, MMO Hall of Fame inductee Wizard101, and the 2007 PC RPG of the Year, The Witcher, for which she was nominated for a Writers Guild of America Award in Videogame Writing. She has spoken at conferences around the globe, including the Game Developers Conference, Game Education Summit, SXSW Interactive, Serious Play Conference, and the Serious Games Summit D.C. She writes about serious games, game design, and other topics on her blog, Game Design Aspect of the Month and can be found on Twitter @sandechen.

Sande Chen is the co-author of Serious Games: Games That Educate, Train, and Inform. As a serious games consultant, she helps companies harness the power of video games for non-entertainment purposes. Her career as a writer, producer, and game designer has spanned over 10 years in the game industry. Her game credits include 1999 Independent Games Festival winner Terminus, MMO Hall of Fame inductee Wizard101, and the 2007 PC RPG of the Year, The Witcher, for which she was nominated for a Writers Guild of America Award in Videogame Writing. She has spoken at conferences around the globe, including the Game Developers Conference, Game Education Summit, SXSW Interactive, Serious Play Conference, and the Serious Games Summit D.C. She writes about serious games, game design, and other topics on her blog, Game Design Aspect of the Month and can be found on Twitter @sandechen.