Underneath the high-crested lights of the Serious Games Showcase & Challenge (SGS&C) showroom that sprawled several football fields last month, 28 game developer teams, including several educational producers, competed for a little recognition and prize money.

Since its 2006 inception, the SGS&C has evolved from a competition aimed at training skills needed by military organizations to a competition with a much broader palate.

“Shadow drone” simulators and combat medic trainers now compete alongside developers whose educational games teach the intricacies of quantum mechanics, and health games that claim to diagnose and treat eye disorders by tracking the player’s eye movements.

“I didn’t want only first-person shooters, or watching Stratego on a screen,” said Kent Gritton, co-founder of the SGS&C and a 28-year U.S. Navy veteran. “There’s so much more that games can be used for. The real value of the gaming environment goes beyond muscle memory: soft skills, communication and adaptability. Those things come out much better in all different types of games.”

Educational developers like three-time-winner Muzzy Lane have enjoyed a modest boost in recognition for, among others, their Mission US educational series. WeWantToKnow’s DragonBox, a critically-lauded algebra app, won SGS&C’s 2012’s award for best mobile game, a category that Gritton said came out of a brief identity crisis for his organization.

Although the Showcase was built to highlight personal computer games, developers were increasingly submitting games and apps meant to be played on iPads or smartphones. The leadership of SGS&C worried the comparisons may not be fair.

“Some of the game experiences were maybe not as rich as something developed for a PC. So we wanted to make sure they were being treated fairly. But how do we keep large companies from competing against somebody who’s developing in their garage? We wanted something with an indie feel, but we realized we were stressing for no reason. Because there’s a market for these types of games, and now 80-percent [of submitting developers] are students who are very skilled. We hope the showcase is an opportunity for educational developers to see that there’s a market for their skills,” Gritton said.

The showcase’s origins lie in strong partnership with the Interservice/Industry Training, Simulation and Education Conference, an annual meeting of national defense minds which featured advanced flight simulators, cyber attacks from fictitious countries and natural disaster scenarios.

The U.S. military has a long relationship with games and simulators, stretching back to at least the late 19th century, when the Naval War College used cardboard ships and grid paper to simulate British naval attacks on New York harbor.

Today, the U.S. Army spends $1 billion a year funding STRICOM, a system of digital simulators designed to expose soldiers to the sights and sounds of war before they ever stomp a boot on the battlefield.

“We did this to ourselves, but it was unintentional. When we put out our very first call for games, we wanted games from the military. But we really have a much more general call now,” Gritton said.

Attracting more SGS&C submissions from educational developers seems to precede recent attempts by I/ITSEC organizers to court potential customers from other industries after government defense budget cuts contributed to a 15-percent dip in attendance from military officials in 2012.

“Whether they’re from academics, government or business, everyone looks at design from a different perspective. It’s very important to get that blended piece. The games must have a specific learning objective, gaming environment, and feedback to the player. It’s all about training,” Gritton said.

That’s a fact some of the developers of less successful submissions don’t immediately grasp according to Lisa Holt, the SGS&C committee chair.

“They’re telling you it’s a serious game, but the instructional aspect seems like an afterthought in the design,” Holt said, who believes a serious game should seamlessly blend both gameplay and instruction.

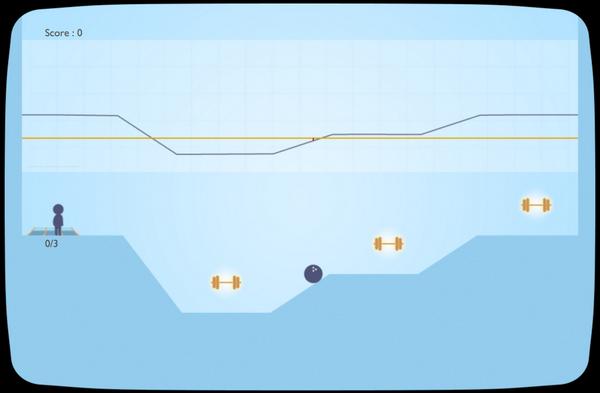

Particle in a Box aims to explain concepts of quantum physics through game play.

According to Holt, this year’s Students’ Choice winner, Particle in a Box: The Quantum Mechanics Game, did exactly that.

Holt should know: she earned her bachelor of science in physics and mathematics and her doctorate in educational cognitive studies, a background she and one additional physics expert brought to bear on GIT’s claims about their games’ potential to teach a subject as complicated as quantum theory.

“From a design and artistic standpoint, it’s lovely, and from a science standpoint, it’s dead-on,” Hold said.

Developed by a nine-person team of students and faculty from the Georgia Institute of Technology, the game earned praise from the Orange County, Fla., high school students tasked with selecting this year’s award.

Holt said she and the rest of the SGS&C staff set up desktop computers, gaming consoles, iPads — whatever they needed to effectively play and dig into the inner workings of a game. The showcase received nearly 30 submissions this year, but Holt said they’ve had up to 50, and they’ve already begun the search for next year’s possible nominees to populate their gigantic showroom floor.

“Early on, some of the educational games we received were a little bit like putting chocolate on broccoli,” said Gritton, “but more and more we’re getting better at providing feedback [to developers] and they’re putting that to heart. The quality of the games and the instructional design has truly gone up in the last 10 years.”