In a computer lab tucked away along a fourth-floor hallway of downtown Seattle’s Central Public Library, 25 coding rookies filled the room to capacity for a chance to participate in this year’s Hour of Code, an event which non-profit organizer Code.org has dubbed the “largest learning event in history.”

Milo Bonet, and his father Rick, arrived early and snagged a seat in the front row. With John William’s iconic Star Wars score drifting from corner speakers, a library technician prepared to guide Milo and 24 others through a coding tutorial with a Star Wars: The Force Awakens theme.

Public Services Technician Chris Ludvigsen explains how to ‘drag-n-drop’ boxes of code during last month’s Hour of Code event in downtown Seattle’s Central Public Library.

Players must help BB-8, the film’s orange-and-white heir apparent to R2D2, collect piles of scrap metal by dragging-and-dropping blocks of code containing simple commands which navigate the little droid around obstacles. It’s a basic mission but is a way to help young kids begin to think in programming terms.

“Yes!” Milo yelled suddenly, one fist pumping into the air, the other gripping a mouse. It took him just a few seconds to figure out the correct coding boxes to drag into his workspace before clicking the ‘run’ button. His father leans in to congratulate him, but Milo has already moved on to the next challenge.

Five additional pairs of adults and kids joined 13 other adults in a coding primer very similar to nearly 200,000 coding events held around the world at roughly the same time.

The events are all part of the non-profit’s huge push to promote their brand of computer science education, and they’ve attracted some big-name attendees from the tech world, including both Microsoft and Apple CEOs. Apple’s Tim Cook and Microsoft’s Satya Nadella, each made personal appearances at nearly identical coding events in East Harlem, N.Y., and Seattle, Wash., respectively.

With endorsement from dozens of NBA players and pop stars as well as President Obama, Code.org has garnered a lot of attention, but what the group really wants is for computer science to count for something more — high school graduation.

Two eager students puzzle over the solution to a Star Wars coding game in downtown Seattle’s Central Public Library during last December’s global Hour of Code event.

Only 28 states allow students to count computer science courses toward high school graduation. The other states allow students to take them as electives only.

Code.org couldn’t make it any easier for a someone to join the push. Their website offers free downloads of form letters to be given to school principals, policy recommendations for local legislators, and even a pre-made slide presentation.

Advocates with a viable “logistics plan” and ties to a Title I eligible school can even sign up to win $10,000 in technology.

Greg Stumph and his daughter Betty also took a front-row seat for the event. Stumph believes adding coding and increasing computer science sources as electives in his daughter’s school could be a good idea, but they shouldn’t be mandatory.

“Betty’s in third grade so she’s starting to be ready for coding,” Stumph said. “She’s into the idea of … those ‘if, then’ things and looping, but not when she was younger. With logic and program structure you get beyond math and just moving blocks around. Those concepts are pretty cool, I think.”

But Stumph also believes his daughter’s school might not be ready to fully incorporate those ideas, and could benefit from some technology upgrades to better teach those skills. It’s an investment he’d be willing to help fund, too.

More than 90 percent of parents want some form of computer science courses taught in schools, according to a survey commissioned by Google in 2013, and Code.org argues that “programming is a critical component to include in a computer science course, and thus only those classes that have some programming should count as computer science. Increasing computer science in schools can help build a foundation for a highly marketable skill down the road.”

Rick Bonet, Milo’s father, is excited about his son’s interest in coding but is not sure about the pitch that coding should be a crucial part of education, saying he’s “just not buying it.” Bonet believes public education shouldn’t simply act as a training ground for workers.

“In that sense, coding is very important because we’re going to need a lot of coders. They could go off and join a team in a [development] studio, but they’re part of a corporation. And corporations are machines that generate wealth for a small minority. So on the face of it, I’m not convinced,” Bonet said.

While Milo’s classmates sometimes talk about becoming baseball or basketball stars, he dreams about becoming an inventor instead. His father thinks coding could help, but worries about the heavy focus on science and math education.

“Getting an education in computer science is a good career move and you can invent a new technology like a smartphone, but that won’t solve all our problems,” Bonet said. “There’s this idea that if you teach STEM, the next generation will come along and they’ll have the tools to solve all our problems. I just can’t believe it works that way. It’s not the technology — it’s us.”

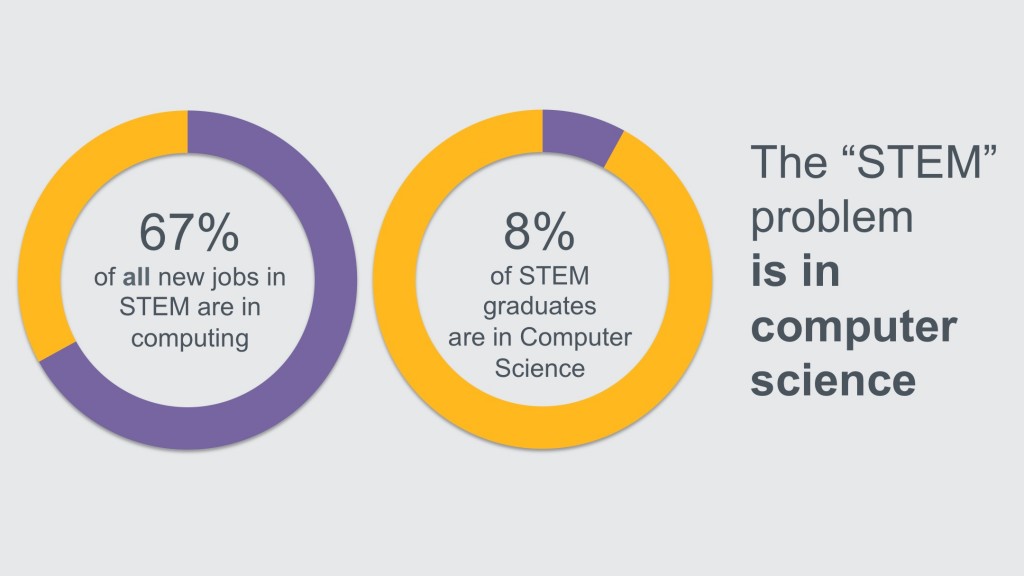

Despite those concerns, Code.org aims to inspire schools to make investments in coding classes by making its case with statistics about the computer science job market, its lack of diversity and the fact that 22 states that don’t allow their students to use computer science course towards their high school diploma.

Part of Code.org’s argument is that computer science is not getting enough attention in STEM education.

Organizations like Code.org are clearly motivated to help rectify the fact that most jobs in the computer science industry are filled by white men. Women represent 23 percent of all U.S. computer science employees, while only 14 percent of those jobs are held by people who are Black or Hispanic.

If these Hour of Code events ultimately have a long-term positive impact on the homogeneous landscape of an industry, the people who filled this particular Seattle computer lab might indicate a positive step in that direction, at least from a gender perspective.

Five of the attendees were women, one who scribbled notes onto a small, yellow pad as the tutorial progressed, and another, Karen Wasserman, who actively sought out the Hour of Code because she was feeling a little out of touch by how little she knew about coding, content management systems and HTML.

“Everybody seems to know about this stuff these days,” she said. Wasserman works as a graphic designer for a local Seattle magazine, and responded well to the tutorial’s drag-n-drop style.

“They’re just pre-built coding blocks,” she said. “There can be many levels of coding knowledge, and you can use those blocks to fulfill a vision or project rather than focus on the really detailed levels of coding.”

Chris Ludvigsen, who facilitated the event but doesn’t come from a programming background, said his most interesting takeaway was the participants who had some coding experience.

“There was a wide range of ages in there. But in the beginning, when I asked who knows about coding, or who has any idea what coding is,” Ludvigsen said, “the only two people to raise their hand were the two youngest kids in the room.”