Ten years ago indie game developer and author Sande Chen studied the state of the games for impact movement in the book she co-authored called “Serious Games: Games That Educate, Train and Inform.” We’ve asked her to revisit that work to see what has or has not changed in the field of learning games.

INTRODUCTION: FUNDING MODELS

When I first studied serious games back in 2005, social media was just beginning. There was no Twitter and no Kickstarter. Now games that likely wouldn’t have interested traditional publishers can get funded through the power of the masses. There have been over 6,000 games funded through Kickstarter with budget goals ranging from modest to massive. The possibility of crowdfunding a game is just one of the positive developments that has emerged over the years.

AUDIO: CONVERSATION WITH SANDE

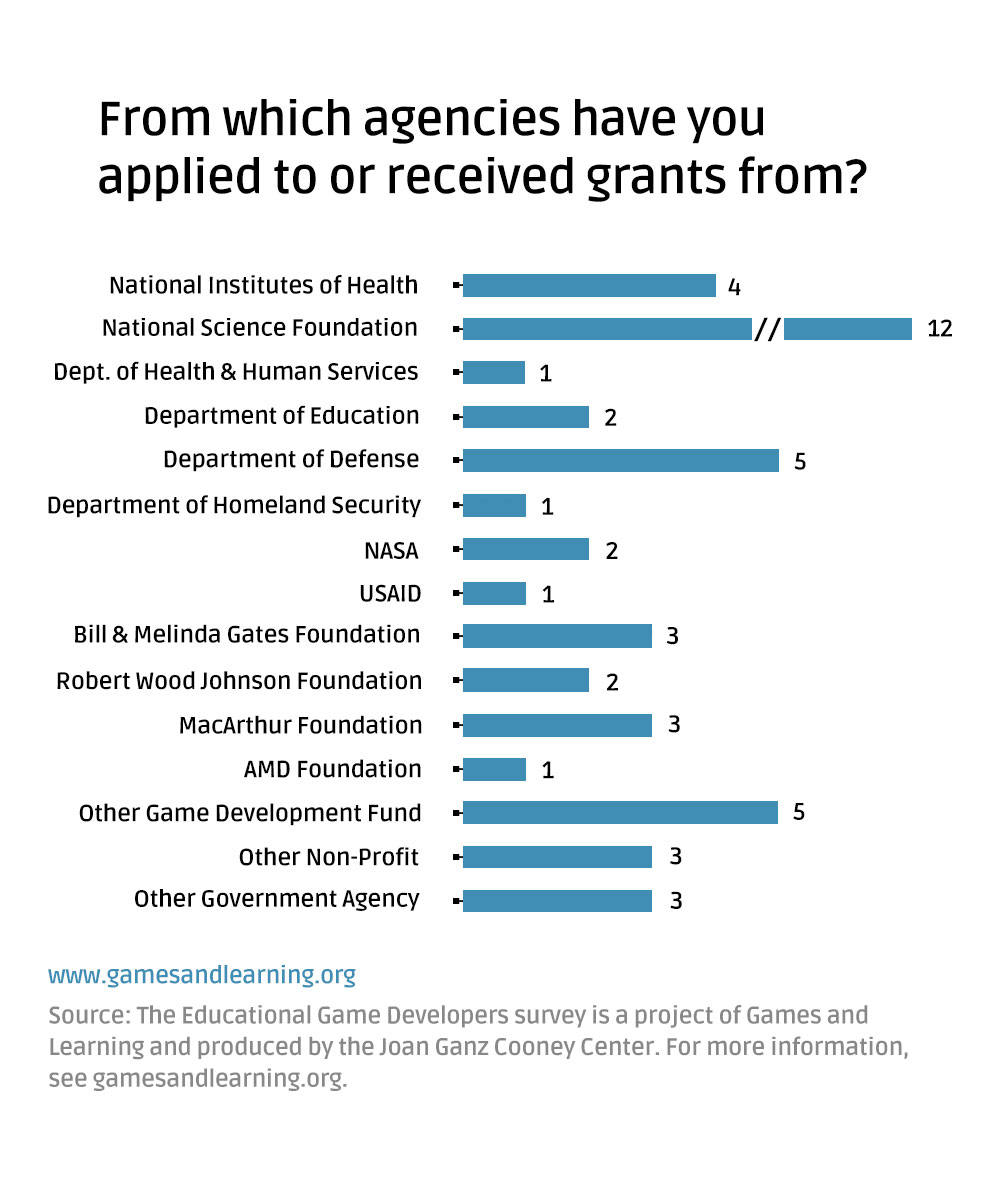

Grants have also taken on added importance. As mentioned in “Is The School Market Still Just a Mirage?,” the Department of Education now funds games, as does the National Endowment for the Arts, National Institutes of Health, and a whole host of other government agencies. Before, game companies could earn grants, but generally with a simulation, a trainer of some sort, or technology that might eventually end up in a game, like facial recognition. Grants from the government or non-profit foundations for games were not common then, at least for independent game developers.

The corporate sector, however, embraced game-based learning early on with games like Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego’s Luggage?, a customer service training tool. Corporations now outspend primary schools on game-based learning, putting dollars into technology they assume will help their bottom line. These firms have also found games useful in recruitment and advertising. That’s why they might be interested in sponsoring a game, especially if it reaches their target audience.

Game developers can also get contract work from textbook publishers that have included more and more interactive elements over the years. Textbook publishers need partners to provide the game design and technical expertise. A good relationship with textbook publishers can mean a steady stream of contract work and ensure that developed games end up in the classroom.

VIDEO: Unofficial Minecraft Trailer

Venture capital plus angel investment is another avenue available to game developers that had not received much notice before, probably because indie developers generally preferred to keep control of their own companies. Microsoft’s 2014 $2.5 billion purchase of Mojang, makers of Minecraft certainly sparked interest in the business world, considering the popular sandbox game reportedly made $100,000 a day. Minecraft, while was developed for general consumers, has been used by over 5,500 teachers around the world.

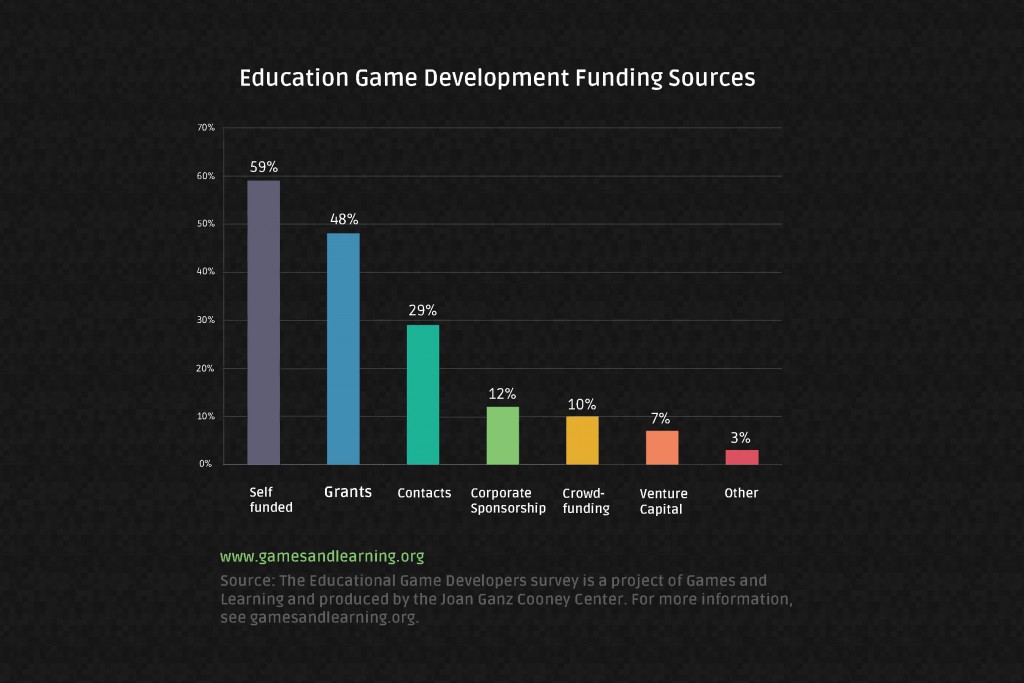

Funding Models

According to the survey, the top three sources of funding for an educational game company are contract work, grants, and self-investment. The largest category, labeled self-funded, could be from reinvestment, loans, or bootstrapping. Any money derived from sales and then funneled back into game development would be considered self-funded. It could also mean that projects were partially funded by another source and supplemented with self-investment.

These categories are followed in popularity by corporate sponsorship, crowdfunding, and venture capital/angel investments. Answers to the “Other” category included projects funded by a university’s internal budget. Often companies use a combination of multiple sources. Matific, for example, is backed by angel investors and the product is sold to schools and parents. Electric Funstuff does contract work and applies for grants. Seekers Unlimited sought to get grants and Kickstarter money to fund games freely given to schools. There are a variety of scenarios.

Just how much money is needed? The survey questions that mirrored the original survey from 2005 were the ones about the production process. For the most part, the results are very similar except that the 2015 data skews more towards newcomers with less experience.

This year there were more projects lasting 1-6 months and more costing $0-$5000. While it’s true that these may be start-ups who used sweat equity, the large number of respondents affiliated with schools could indicate students or researchers who did not factor in industry level labor costs. In 2005, the budget range of $100,001-$500,000 had the most responses, though $0-$5000 was considerable too. For both surveys, team sizes of 1-10 were preferred.

Never mind what the application is, the process alone of submitting the grant online is complex.

— Karen Littman, Morphonix

Grants

In the last few years, grants have increased in importance to educational game developers. Grants come from various sources: non-profit foundations, governmental agencies, even game development or media funds.

STAT: Developer Survey

Some grants are awarded only to non-profits and so a game developer can partner with one, typically a university, think tank, or museum. Grants can come also come with strings attached, such a requirement to make a version of the game free to the public. That could be accomplished by making the Web version free while the App version is for sale. The $200,000-$500,000 infusion that typically comes from a grant can really make a difference to a small game developer.

Of particular note, the U.S. government’s Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program has no restriction on commercialization. That’s right; the government wants you to sell games and unlike with contract work, the developer retains full ownership of the game. Created in 1982, the SBIR program awards more than $2 billion each year for research and development.

Karen Littman of Morphonix, who has received several multi-million National Institutes of Health (NIH) SBIR grants over the course of 25 years to develop games about the neurosciences, hires a psychiatrist to lead the research component. In the past, Littman worked with university researchers, but found there sometimes the university partner wanted more of the resources. By moving the research in-house, she has much more control over the studies and also, the production.

The SBIR program has three phases. Phase I, which can be as much as $150,000, is a test of feasibility. After Phase I is completed in six months or less, companies can apply for Phase II, which awards up to $1 million over the course of two years. The key goal of Phase II is the development of a prototype with the intent to commercialize. Phase III, commercialization, is not funded by SBIR program. Companies are expected to secure private investment or funding from other government sources.

Each of the 11 federal agencies in the SBIR program allocates 2.8% of its R&D budget to these grants. That means agencies with the larger budgets have more funding for SBIRs. For instance, the well-funded Department of Defense accounts for more than half of all SBIR spending and the lesser-known Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) grants. When asked about grants in the 2015 survey, 27% of respondents answered that they had authored a SBIR, STTR, Broad Agency Announcement (BAA), or similar government RFP, compared to 16% in 2005.

Despite the increase in the number of developers requesting grants, the process is anything but simple. Companies can take months preparing the application because it needs to be done in a very specific manner. It’s gotten more competitive over the years and seemingly more complex. Each agency has its own focus or idiosyncrasies and so each agency needs to be approached separately.

“Never mind what the application is,” says Littman, “the process alone of submitting the grant online is complex.”

Once the application is submitted, it can take anywhere from 3 months to a year to see if the project meets approval. If it doesn’t win approval, the company can revise and re-submit at the next opportunity. Some companies apply for several grants at one time, hoping to get at least one grant. It’s a lot of uncertainty.

Since Phase II funding is contingent on Phase I approval, a company can be without funding while waiting to learn if it has gotten Phase II. In the best-case scenario, the wait is only the rest of the year. However, there is a faster way. Littman uses the Fast-Track application, which allows for one application for Phase I and Phase II together. For Littman’s most recent Fast-Track application, she applied and heard back in a year. She received the Phase I grant money first and after submitting the first report, received the rest of the funding. It’s not an upfront payment, but paid out as expenses are submitted.

Littman offers these tips on navigating the grant application process: “I always suggest to people that they should ask for help. When I first started doing this, the project officers who work at these agencies were extremely helpful in helping me to go through the process. That’s their job.”

While Littman and others have succeeded in getting a steady stream of grants to fund game development, others have not. One-time funding isn’t going to keep a game developer afloat. If a developer can’t get more grants, it will have to seek other ways of funding.

It’s very collaborative. They bring their subject expertise and we apply our specialty: game design and thought leadership.

— Brandon Pittser, Marketing Director at Filament Games

Contracts & Corporate

Contract Work

Contract work isn’t glamorous but it pays the bills.

An educational game developer can survive as a client shop building games for one or more of the big textbook publishers. As with schools, this is a business based on relationships. The three major players in the textbook publishing world are Pearson, McGraw-Hill, and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Together, they dominate the education market. Typically, if there was work to be had, the textbook publishers would send out a RFP to known vendors. Once in that inner circle, a developer could quickly become the go-to for that kind of work. Usually, it’s work-for-hire, but in some cases, developers have negotiated for royalties or other fees.

Brandon Pittser, Marketing Director at Filament Games, says his firm has found contract work a decent way to make good games, noting, “It’s very collaborative. They bring their subject expertise and we apply our specialty: game design and thought leadership.” However, relationships differ. Other developers have complained that textbook publishers still don’t get what games are about and continue to ask for interactive worksheets or quizzes disguised as games.

Amplify tried things differently. They contacted indie game developers whom they thought would make awesome educational titles. They encouraged the developers to pitch ideas and lead the development process. Budgets varied per project. Amplify didn’t mind working with young developers but tended to stick with established indie developers with good track records.

“We know they know how to make games,” Joe Mauriello, Lead Game Design, Research, and Customer Experience Manager at Amplify, says of the companies they hired. “We provide support with curriculum expertise and the playtesting but we want to make games that people are going to want to play.”

While contract work can give steady income, its not a panacea for the developer. First, it only lasts as long as the contracts do. Therefore, it’s always better to have more than one source of funding. Secondly, work-for-hire agreements usually means that the company doesn’t own the rights to its own work but of course, this is subject to negotiation. Amplify did have one developer who went ahead and used its contracted educational game as a template for a subsequent entertainment title.

Corporate Sponsorship

Corporate sponsorship is perhaps the trickiest of funding sources to use due to ethical concerns about marketing to kids. Critics say that sponsored games are just another form of advertising. Parents, already wary of in-app purchases, are jittery about exposing young kids to any form of advertising in games.

Moreover, game developers need to obey the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) and if caught disseminating personal information about a child under age 13 for whatever purpose, even marketing, could be subject to a $16,000 fine. On top of that, there could be strict child privacy laws from the state level.

Product placement may be less intrusive but sharp-eyed parents may still have complaints even if the educational content is unchanged. Product placement and promotion of consumer products may also violate state standards. Besides schools, museums may have a problem with corporate sponsorship, even if it’s just the addition of a company logo. Kellian Adams, founder of Green Door Labs, learned this when a well-known museum refused to accept a corporate sponsor on a project, forcing her to scale back.

Still, schools have not had a problem when corporations want to help publicize social causes, like conservation. EverFi, whose business model includes corporate sponsorship, gives its interactive courses to schools for free and says there have been no complaints. In this course about STEM topics, Future Goals – Hockey Scholar, all the activities are focused around hockey and there is a disclaimer that it was sponsored by the NHL and NHL Players’ Association.

When approaching corporate sponsors, think about what would be compatible with the game. If it’s a game about recycling, would a waste management company be suitable? Think about the game’s target demographic and why it would be advantageous for the corporate sponsor to reach this age group. If done tastefully, corporate sponsorship may turn into a mutually beneficial partnership.

Crowdfunding

Crowdfunding is basically pre-orders combined with incentives. Interested funders select a tier, which could be anywhere from $1 to $10,000, pledge the amount stated, and then become entitled to the rewards for that tier. Rewards could be credits in the game, early access, virtual items, box copies, visits to a school, really anything. In return, the developer needs to follow through with the promises and provide updates on the game’s progress.

Kickstarter campaigns are intense affairs.

As soon as they start, there’s a ticking countdown, typically lasting 30 days, to reach the projected goal. Successful campaigns tend to launch an all-out social media PR blitz for the game because a developer will need to attract more than just friends and family to succeed.

The traditional PR methods also work. Judy Tyrer, who successfully went through a Kickstarter to fund 3 Turn Productions’ massively multiplayer game, Ever, Jane, put advertisements in related magazines and sent press releases to university newspapers in addition to posts on social media. This got the attention of what’s known as an influencer, who can turn a campaign into viral gold.

VIDEO: Moonbase Alpha

Tyrer has this piece of advice for developers who are gearing up for a crowdfunding campaign: “Never say ‘No,’ no matter how small the press is. It trickles up.” It doesn’t matter if the interview is with a YouTube channel with only 500 subscribers. Maybe that video interview gets through to a blogger, who in turn is quoted on a gaming website, and so forth. Anything can get anywhere through word of mouth.

Of the 4 survey respondents who had successful crowdfunding campaigns, one was in the $5001-10,000 range, two at $10,001-$50,000, and the last one, which came from Judy Tyrer, surpassed $100,000. Of the interviewees, two had conducted Kickstarter campaigns. One had surpassed its initial goal of $8,000 but had to find additional funding to finish the project. The other failed to reach its $15,000 goal.

Virtual Heroes recently launched a Kickstarter to make a sequel to its multiplayer astronaut game, Moonbase Alpha, but failed to reach its goal of $480,000. The original game, available for free on Steam, was funded by NASA and the Army’s Aviation Missile Research Development and Engineering Center with the aim of encouraging young people to pursue STEM fields.

Venture Funding and Angel Investment

According to market research firm Ambient Insight, global investments in game-based learning companies reached $106.3 million in 2014, compared to $12.6 million in 2010. In just the first half of 2015 alone, investments in the sector tally up to $83.6 million. There are currently 613 educational game start-ups on the Angel List as of September 2015. In addition, there are product accelerator programs like co.lab and Pearson Catalyst for Education.

Of the investments tracked by Ambient Insight, all of the mobile game-based learning companies that received funding in 2013 were developing games for young children. This market segment is a proven revenue generator, dominating the global market in mobile game-based learning. Other proven winners are brain trainers and language learning programs, and a new opportunity may be arising in computer programming.

The NewSchools Seed Fund reports that their 2013 venture funding for companies focused on teaching computer science or programming to young students jumped to $23 million from $1 million in the previous year and believes that this will be a growing trend due to the increasing need for schools to include such curriculum.

VIDEO: Hakitzu Elite

Just recently, Mayor Bill De Blasio announced that by 2025, all public schools in New York City will be required to offer computer science to all students. The San Francisco Board of Education intends to make computer science education mandatory through 8th grade and Chicago wants to make computer science a requirement for high school graduation by 2018. Last year, the UK Department of Education mandated programming curriculum in all primary and secondary schools and launched a glitzy Year of Code campaign to encourage people to learn programming. Consequently, there is a need for tools to teach computer science or programming.

There is no shortage of game companies with games that teach programming or game design. Many such companies, like New York’s Hidden Level Games, already work with schools in workshops or after-school programs. London-based Kuato Studios has seen Hakitzu Elite, its robot combat game that teaches JavaScript, used in classrooms.

To be considered by venture capitalists and angel investors, a start-up company needs to show good growth potential. It helps if it’s scalable, able to ramp up quickly, and if the product can’t be easily duplicated. It also helps to have a management team experienced in start-ups.

Conclusion

There are educational game companies who are surviving and thriving by relying on one or more of these funding sources. Educational games have gotten the attention of corporations, investors, government officials, educators, and gamers who believe these games are effective ways to advertise, innovate, and educate. With more funding sources available, the industry has the means to continue on its path.

“I think the space has grown tremendously with a lot of great work,” says David Langendoen, co-founder of Electric Funstuff and recipient of a 2013 ED SBIR. “The only hope is that we continue to generate quality games and keep learning as an industry.”

However, as the survey indicates, a majority of respondents feel that even more public and private funding is needed before improvements can be seen. The question remains: Are these funding streams sufficient to build a sustainable business? While those backed by venture capital are expected to make a profit, a company funded by self-investment, contract work, grants, crowdfunding, or corporate sponsorship may never create or commercialize its own game. And there’s the uncertainty of never knowing if the grant came through or if there’s more contract work on the way.

In 2009, after evaluating the business of serious games, Merrilea Mayo, then of the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, discovered that games supported by grants or made in universities don’t tend to get proper marketing. One reason could be that academics are rewarded more for peer reviewed journals than the commercial success of a game. Furthermore, it takes money to market a game, generally 40-50% of the budget. Mayo did think that adult hobbyists might be interested in these educational titles.

Littman says, “For an educational game company that doesn’t have a lot of venture capital, we’re well-funded but it isn’t enough for distribution and marketing.” Adams and Will Penner, a sole proprietor selling one game, also cited distribution and marketing as major hurdles.

Mayo’s recommended non-profits and government agencies help educational game developers bridge this gap from start-up to commercial success. But there is one change she hadn’t expected. The next article will explore this seemingly unlikely occurrence: entertainment game developers with educational initiatives or versions.

Welcome MinecraftEdu.

Sande Chen is the co-author of Serious Games: Games That Educate, Train, and Inform. As a serious games consultant, she helps companies harness the power of video games for non-entertainment purposes. Her career as a writer, producer, and game designer has spanned over 10 years in the game industry. Her game credits include 1999 Independent Games Festival winner Terminus, MMO Hall of Fame inductee Wizard101, and the 2007 PC RPG of the Year, The Witcher, for which she was nominated for a Writers Guild of America Award in Videogame Writing. She has spoken at conferences around the globe, including the Game Developers Conference, Game Education Summit, SXSW Interactive, Serious Play Conference, and the Serious Games Summit D.C. She writes about serious games, game design, and other topics on her blog, Game Design Aspect of the Month and can be found on Twitter @sandechen.

Sande Chen is the co-author of Serious Games: Games That Educate, Train, and Inform. As a serious games consultant, she helps companies harness the power of video games for non-entertainment purposes. Her career as a writer, producer, and game designer has spanned over 10 years in the game industry. Her game credits include 1999 Independent Games Festival winner Terminus, MMO Hall of Fame inductee Wizard101, and the 2007 PC RPG of the Year, The Witcher, for which she was nominated for a Writers Guild of America Award in Videogame Writing. She has spoken at conferences around the globe, including the Game Developers Conference, Game Education Summit, SXSW Interactive, Serious Play Conference, and the Serious Games Summit D.C. She writes about serious games, game design, and other topics on her blog, Game Design Aspect of the Month and can be found on Twitter @sandechen.