Introduction

Amid a boom in investment and experimentation with educational technologies in U.S. schools, digital games are gaining a strong foothold in the K-8 classroom, as teachers report incorporating video games in their curriculum with positive results. A national survey of nearly 700 U.S. K-8 teachers conducted by the Joan Ganz Cooney Center and the Games and Learning Publishing Council reveals that almost three-quarters of K-8 teachers are using digital games for instruction. Four out of five of those teachers report that their students play games at school at least once a month.

In his introduction to the critical survey of classrooms GLPC Chair Milton Chen observed:

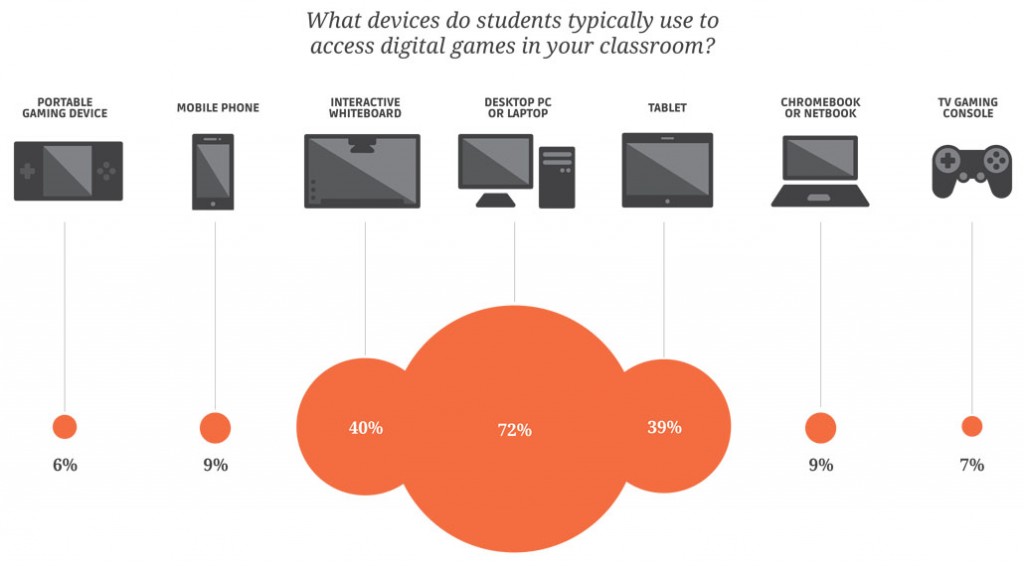

Two fundamental findings should capture the attention of all educators, developers, funders, and policymakers: a majority of teachers are using digital games in their classrooms, and games are increasingly played on mobile devices that travel with their students.

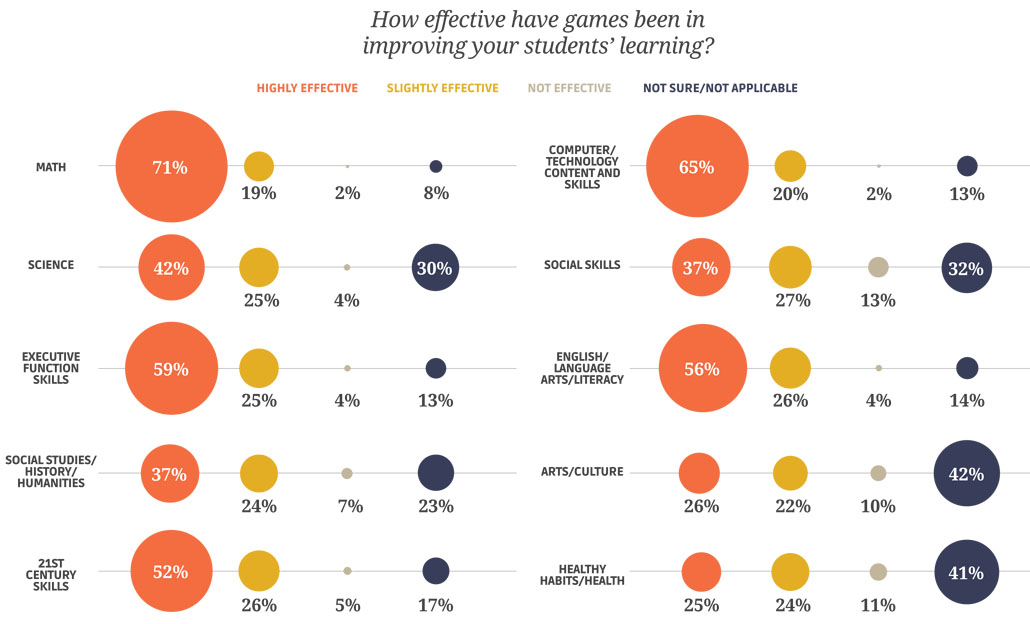

Level Up Learning: A National Survey of Teaching with Digital Games by Lori M. Takeuchi and Sarah Vaala reports that teachers who use games more often found greater improvement in their students’ learning across subject areas. However, the study also reveals that only 42% of teachers say that games have improved students’ science learning (compared to 71% in math), despite research suggesting that games are well suited for teaching complex scientific concepts.

Although technology in the classroom is evolving from computers to tablets, a new survey from the Games and Learning Publishing Council highlights that the use of digital games in the classroom is becoming more common and teachers are increasingly valuing the ability games have to motivate low-performing students.

Gamers in the Classroom

Digital games are becoming a more regular part of the classroom, according to the nearly 700 teachers who responded to the survey.

Digital games are becoming a more regular part of the classroom, according to the nearly 700 teachers who responded to the survey.

Digital games have landed in K-8 classrooms.

Nearly three-quarters (74%) of K-8 teachers report using digital games for instruction. Four out of five of these teachers say their students play at least monthly, and 55% say they do so at least weekly. Digital gameusing teachers also say they’re using games to deliver content mandated by local (43%) and state/national curriculum standards (41%), and to assess students on supplemental (33%) and core knowledge (29%).

Who’s using games with their students?

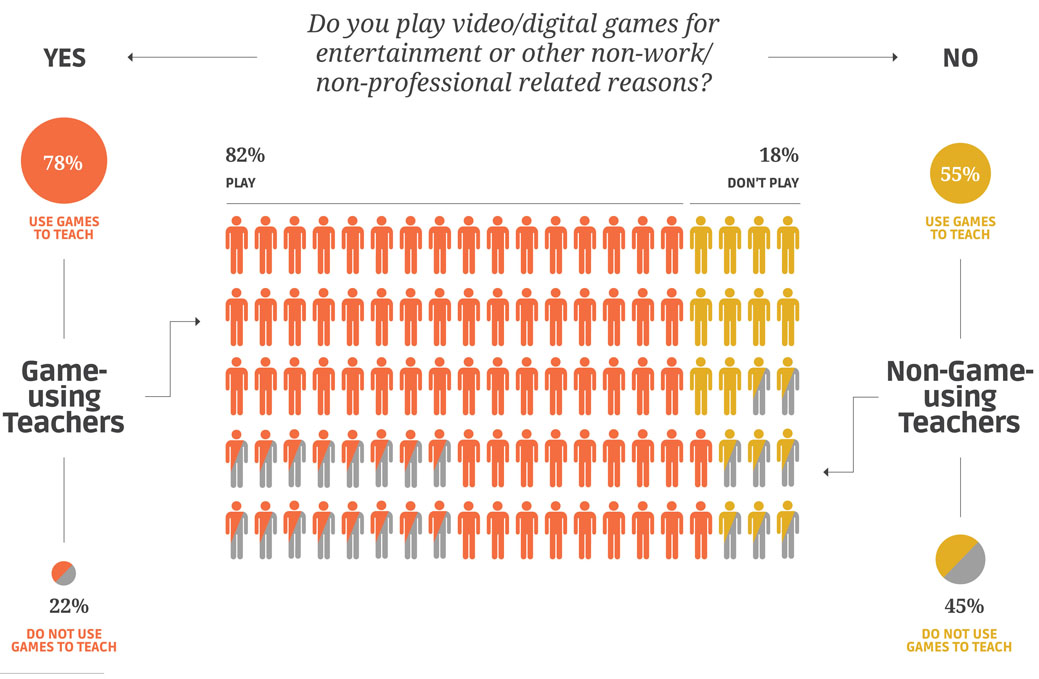

Gender does not predict digital game use in instruction, but younger teachers, those who teach at schools serving low-income students, and teachers who play digital games for their own pleasure are more likely to use games with their students. Younger teachers and those who play digital games frequently let their students play more often, too. In turn…

Teachers who use games more often report greater improvement in their students’ core and supplemental skills.

Coincidentally, the teachers that use games more regularly also use games to hit a wider range of objectives (teach core and supplemental content, assess students) and expose students to a wider variety of game genres and devices.

Educational games rule in K-8 classrooms.

Four out of five game-using teachers say their students primarily play games created for an educational audience, compared to just 5% whose students most often play commercial games. Eight percent of game-using teachers say their students mostly play a hybrid of the first two options—entertainment games that have been adapted for educational use.

The one big barrier that separated the game-using teachers from the non-game-using teachers was that non-game-using teachers were more likely to say that they found it very challenging to integrate games into instruction.

— Lori Takeuchi, author of “Level Up Learning”

Mixed Messages

Although the report found that use of games has moved from the more experimental classrooms into the mainstream, the authors still found areas where teacher attitudes appeared to be evolving.

Lori Takeuchi, head of research at the Joan Ganz Cooney Center and lead author of the report, said teachers’ belief in the possibilities of games sometimes did not align with how they actually view them.

“Teachers are trying to use games to cover core curriculum content and supplemental and they are also trying to use games to assess students,” she told gamesandlearning.org, adding, “The teachers don’t list the assessment properties of games to be one of their greatest strengths,… despite the fact that these teachers are saying they want to be able to use these features of games.”

Another reality the research highlighted was the still-intensely personal way in which the use and integration of digital games is spread.

“48% say they rely on what other teachers say about games and only 15% turn to reviews. This mirrors what is happening with how teachers learn to use games in the classroom,” she said, adding that, “It is great to have the personal connection with a fellow teacher, but it also limits what they think may be possible with digital games.”

To be able to customize tools, programs, and pathways that can more effectively meet the diverse needs of K-8 teachers who want to bring digital games into the classroom, developers, school leaders, trainers, and other stakeholders need clearer images of the individuals they’re designing for.

— Lori Takeuchi and Sarah Vaala

Teacher Profiles

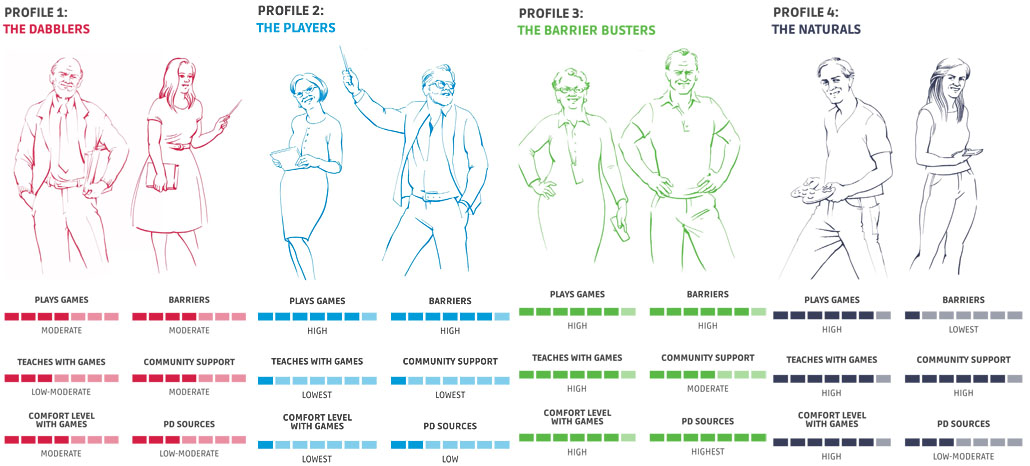

The researchers found as they examined the types of teachers that used digital games in the classroom that they were as unique and individual as the students they taught, but still they found groupings of teachers facing similar challenges and possessing similar comfort levels with games.

“We weren’t satisfied to only compare teachers who use games in the classroom to those who do not, however,” co-author Sarah Vaala wrote in a post at the Cooney Center. “A prime goal of our study was to explore different patterns of game-use in the classroom, including both the frequency and nature of digital game use in teaching.”

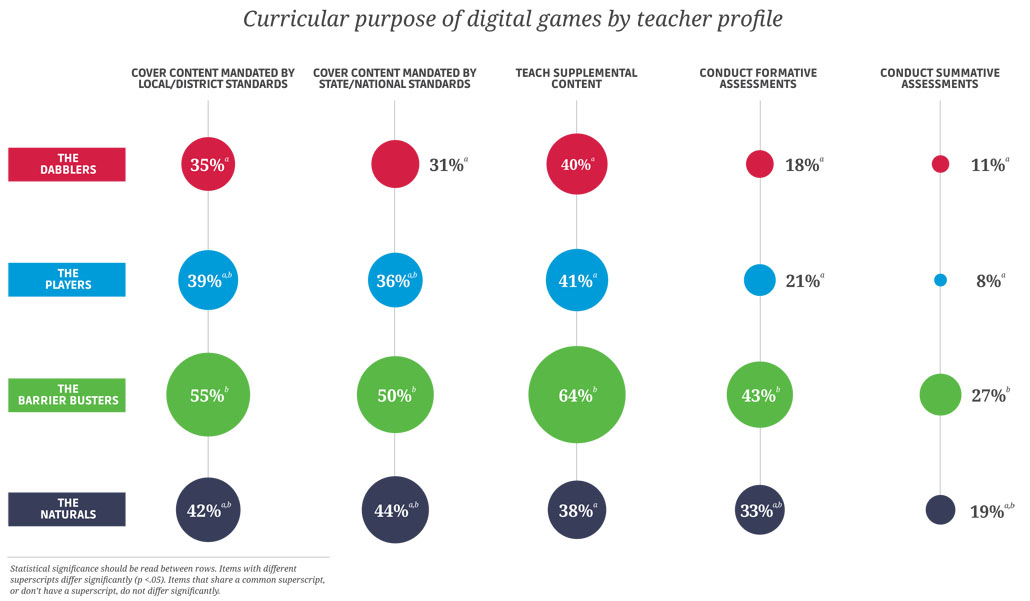

What emerged from their analysis were four general composite types of teachers that use games.

Dabblers

These are teachers who are not gamers themselves and report fairly low levels of comfort with the technology. This group, which made up about 20% of the teachers that use games, is the most conservative when it comes to using games and the most likely to use personal computers versus tablets or game consoles.

Still, the report found, “While Dabblers hold lower confidence in the efficacy of digital games to teach 21st century skills than the others, they are still more likely to indicate positive or no changes than negative changes in student behavior and classroom management as a result of” game-based teaching.

The Players

Perhaps the oddest group to consider, “The Players” were a group of teachers — about 23% of teachers that use games — that play games themselves but rarely use them in class. This group turned out to be the teachers who use digital games the least and, although the research cannot draw a direct connection, it may have a lot to do with where they teach.

The report found that, these teachers “Face many barriers when using games with students—the highest reported among all groups—and receive the lowest levels of support from parents, administrators, and fellow teachers.”

Barrier Busters

One key thing seemed to separate the Barrier Busters from The Players and that was faith in the power of games to teach. Like The Players, these teachers are themselves gamers and also face significant barriers — money, time, etc — to implementing games.

But unlike The Players, Barrier Busters aggressively seek out information about how to integrate games into the classroom and are very likely to use them.

Barrier Busters “provide students with access to the greatest variety of game devices and genres. They also use digital games at significantly higher rates than their fellow [game-using teachers] to deliver curricular content and assess students.”

The Naturals

The last subgroup the report identified were those teachers who did not need much support or professional development to implement games. These teachers, The Naturals, have access to supportive communities and use their games for many of the most creative purposes.

As the authors put it, “Report a moderately high variety of game device and genre use. Notably, this is the only profile that uses games to deliver core content more often than supplemental content.”

Recommendations

The report includes a variety of recommendations for teachers, developers and policymakers to consider as a way to unlock what most teachers describe as the ability of games to both engage and educate.

Several of the recommendations focus on improving the training of teachers — the report actually finds only 8% of teachers receive pre-service training on using and integrating digital games. The authors call on funding more experimental programs and developing a universal system of training as well as the digital tools to assist with that training.

Still, the report cautions, “Certain institutional factors, such as high-stakes testing and the partitioned structure of the school day (especially in middle school), will need to change before immersive games can have a real presence in K-8 classrooms.

For the full recommendations and an enormous amount of data and analysis, download the full report.

Methodology

This survey was designed by the Joan Ganz Cooney Center and was fielded during a three-week period in Fall 2013 by VeraQuest, who recruited respondents from the uSamp online survey panel. The panel has over 2 million members in the U.S. who have been recruited through a number of different panel enrollment campaigns, and panelists are required to double opt-in to ensure voluntary participation in the surveys they are invited to complete. Adult respondents were randomly selected from a targeted uSamp panel of k-8 classroom teachers to be generally proportional of the demographic strata of total U.S. teachers. Once selected, respondents were invited to a protected web-based survey which ensured that only the intended recipient could complete the survey, which could be completed only once. There were 694 respondents from the U.S. who reported being classroom/specialist k-8 teachers who completed the survey.

Statistical testing completed at 90% confidence level where appropriate. In some instances percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding.

Photo Credit

The photo at the top of this page was taken by Barry Joseph and documents the the MicroMuseum Day-long session. You can see more of Barry’s photos on his Flickr page.