Earlier this week we published the first part of a major survey of those community organizations and schools that serve low-income students. The results indicate that while technology is increasingly available to the people who run these programs and teach in these classrooms the access to technology is far from uniform and often lags behind wealthier communities.

That said, an impressive 47% of teachers and school administrators and 34% of out-of-school program directors and instructors have expressed interest in learning more about using game consoles and other gaming tools to teach. Today, we look at what are the major impediments to those educators unlocking the power of game-based learning and other e-learning tools and what designers can do to respond.

Barriers to Adoption

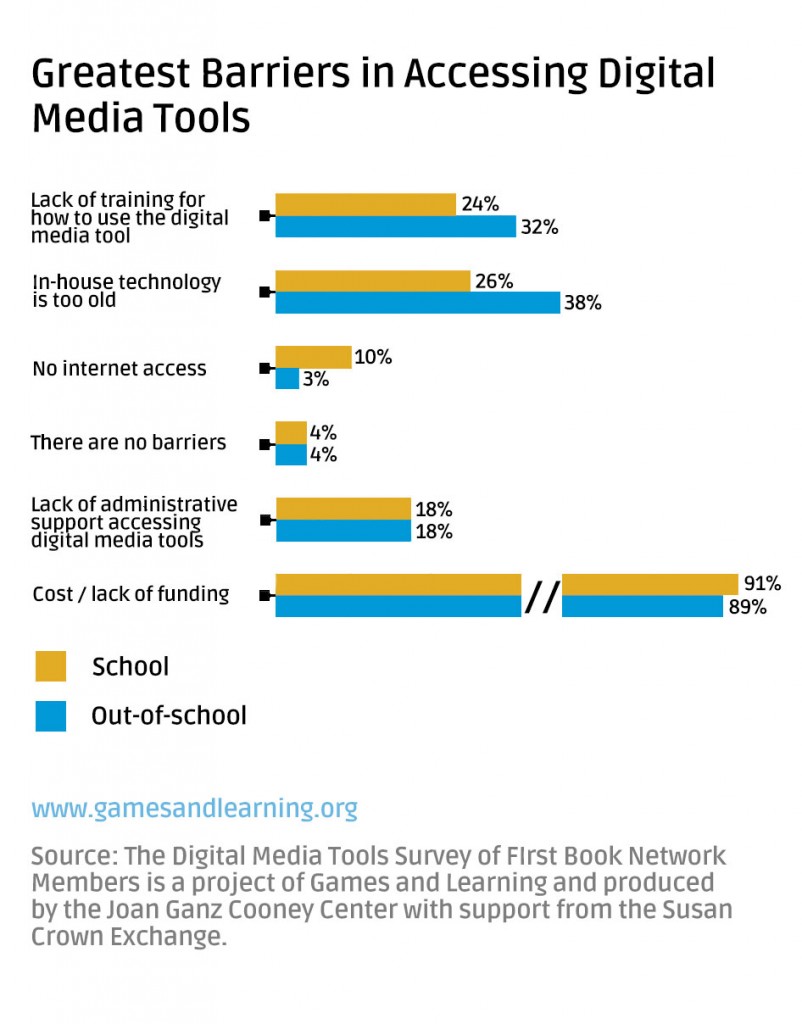

The barriers to the use of games and other technologies echo what we have heard before from general surveys of teachers. Still, for those serving lower-income students the challenges often are more complex than in other schools. The big three barriers both in- and out-of-school folks reported were

The barriers to the use of games and other technologies echo what we have heard before from general surveys of teachers. Still, for those serving lower-income students the challenges often are more complex than in other schools. The big three barriers both in- and out-of-school folks reported were

- Cost

- The age of technology

- Lack of training

Cost is by far the largest issue. Schools (89%) and out-of-school programs (91%) both reported it as a barrier and even when they have access to technology, cost may prevent effective implementation of it. For example, one teacher in a Title I school reported, “Our school of 300 was given 10 iPads to use in our classroom. As you can guess, they are never available for the majority of our kids.” Especially in formal education, people said that technology funds often flowed to higher performing schools and left their programs under-equipped to deal with students who may have disabilities or not speak English as a first language.

And even when they do have technology, there is often not enough, as the earlier comment indicated, to go around. Of teachers in schools that serve low-income 39% specifically mentioned that they had some amount of technology available to them, but that there were not enough devices to go around.

Both groups also noted the age of technology as a problem, noting they did not have the newer tools like tablets and were instead left with aging desktops that were unreliable.

It’s a reality that veteran app developers caution others to be keenly aware of when mapping out their development strategies. In discussing the findings, Neal Shenoy, founder and CEO of Speakaboos, a reading application aimed at young students, stressed the need for developers to better understand the reality of the classroom.

Most development work, especially in edtech, is done in New York, San Francisco, maybe L.A., Boston and maybe D.C. and for the most part definitionally bubbles. Our experiences of how we consume media and hardware are radically different than most of the United States, let alone the world… If a developer saw that in your design of an educational product there is a tremendous amount of platform disparity, virtually no IT support, cost has to be rational, bandwidth is light and as sort of an icing on the cake you want build in a bridge to parents. If you knew that up front, and luckily we did, then we would design for that… If you design for that up front you save enormous costs.

— Neal Shenoy, Speakaboos

He went on to add that although there are clear cost implications for designing across multiple platforms, the flexibility of the tool could greatly expand the possible markets for the developer. For those thinking about how to design for lower-income communities and market Shenoy said, “I think you have to design for a smartphone. The next level up is really a laptop or computer usage. We haven’t seen profound tablet penetration in low-income, but smartphone absolutely and computer somewhat.”

Even for those schools that had the equipment or managed to fund some technology, many teachers noted that schools and other programs lacked the training for students and teachers. One media teacher who helped implement technology in school had a lengthy observation that captured many of the thoughts we heard from both sectors, saying, “The reasons for barriers to technology are multi-layered. In the school where I was the school media sub and a member of the tech task force, many kids at this Title I school had no computers at home and lacked basic keyboarding skills… Internet connections are poor and affect online testing performance. Expensive replacement bulbs for projectors result in unused projectors. Lack of training on whiteboards and whiteboards incompatible with certain hardware mean they sometimes go unused! Schools need to spend more time teaching proper use and care of technology to students who are assumed to be tech savvy. Students have inadvertently erased drives, banged keys in frustration with slow computers, and jammed keys by not washing hands after lunch and gumming up keys… The school media teacher is one of the best people to lead the technology efforts across the curriculum. Teachers may have a narrow view of how to use the technology and may not fully utilize the media specialist.”

Those schools aggressive enough and savvy enough to go after grants even suffer in this area with one instructor noting, “I have won several technology grants from Samsung, but would like specific training to better utilize what I have.”

Despite the challenges these school and non-school instructors and administrators reported there are significant opportunities for digital tool developers in both markets. First of all, the out-of-school market lacks the highly structured and often inflexible purchasing systems that can complicate in-school purchasing. And both formal and informal educators express keen interest in learning more about game-based learning and using mobile technologies to engage students.

Both groups cite wanting content and tools that can be easily modified for use in a program or classroom and so longer, linear games are less likely to work for either group. They both also note they look for content that is based in research into serving young people and, for schools in particular, have a proven track record of helping kids do better.

Of particular note for developers, out-of-school programs as well as many school teachers note that they would prefer content that better reflects the cultural and ethnic diversity of the students they serve.

Diverse Programs

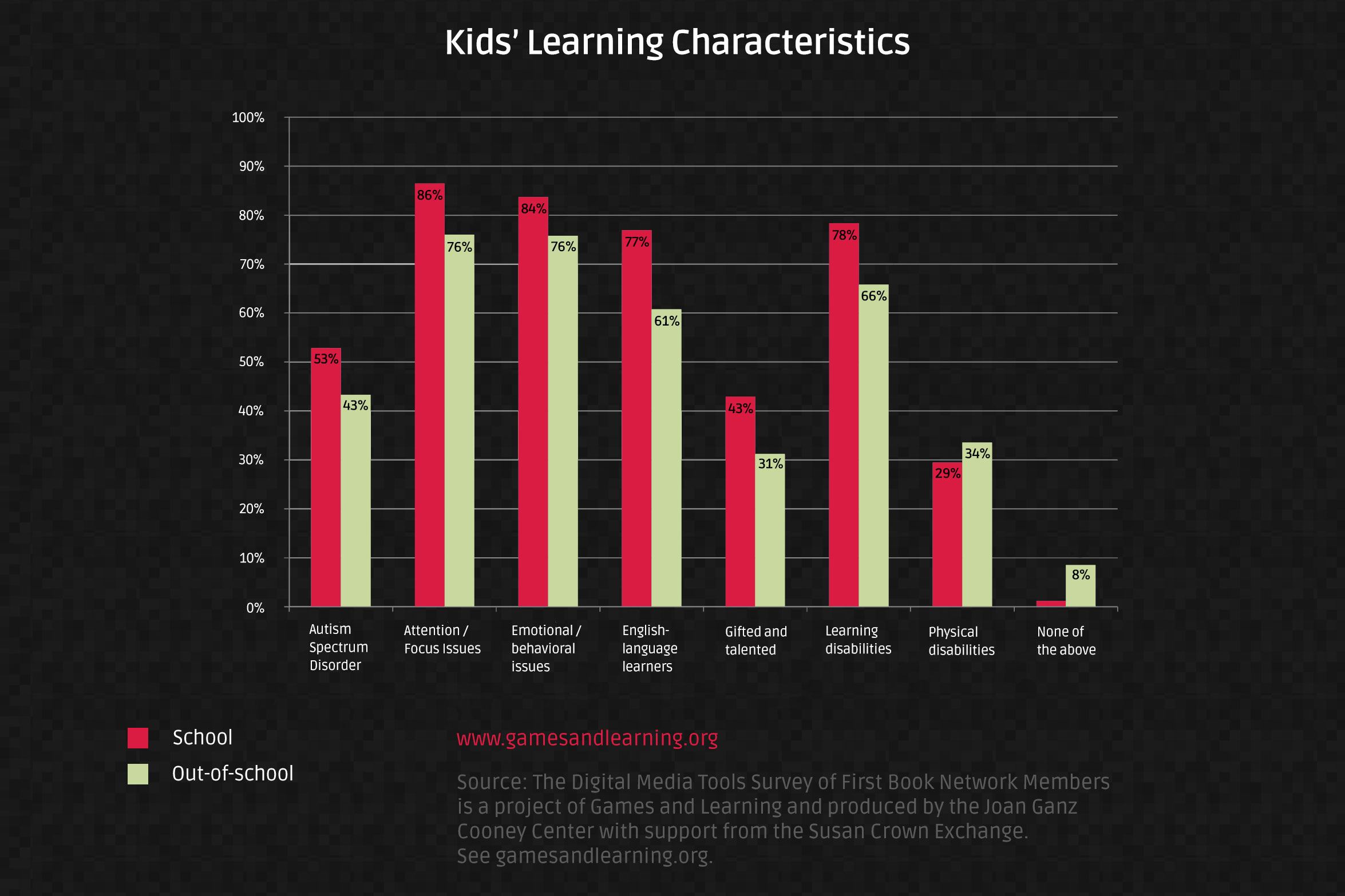

And that is another of the striking things we found was the wide variety of learning characteristics these teachers and instructors face. As noted, the vast majority of teachers report students have problems maintaining attention (86%) and emotional challenges (84%) and many report that they are teaching to children for whom English is not their first language (77%).

In their responses, the teachers noted that for many children learning English as well as other curricula technology often presented new problems, with one teacher noting, “I work with Hispanic families. The parents of these families have had little to no training on digital technology, making sharing of information with them more difficult during our weekly home visits. I am constantly searching for ideas to share with them in Spanish, and give them a bit of training along the way.”

Out-of-school programs report many of the same types of numbers.

For both in-school and out-of-school respondents, the stress of finding the resources that hit the sweet spot of scaling to serve gifted students and also reaching those students who may be struggling or overcoming disabilities was heard throughout the comments. One teacher pleaded, “How many hours at home should I spend researching new apps, trying them out and paying for them on my personal device to see if it will help students learn? Not all educational apps and programs are really educational, and now it is completely up to the teacher to figure out what works. I love the potential for technology in education; I hate having another aspect of education that I must spend more of my personal time and money on to make it work.”

Methodology

This survey was designed by the Joan Ganz Cooney Center and was fielded during an 11-week period in the Summer of 2015. The survey was sent out to the 185,000 members of the First Book Network. First Book is a non-profit that seeks to help those organizations within school and in the community that serve low-income kids. The network now has 200,000 members. The research was made possible by a grant from the Susan Crown Exchange. Some 1,459 First Book Network members responded and of those filling out the survey 988 worked in formal education and 471 work in out-of-school programs.

Photo Credit

The photo at the top of this page was taken by Dan Lundmark. You can see more of Dan’s photos on his Flickr page.