A new guide aimed at helping teachers incorporate games into the classroom offers developers of those games some important insights into the potential and the obstacles to bringing game play into schools.

The guide, produced by the KQED site Mindshift and largely written by Forbes contributor and professor Jordan Shapiro, covers critical topics for teachers like what the research says about using games to teach as well as screentime for younger children as well as helping and more practical guides to how to select and incorporate games into the classroom.

If you’re building a game for the classroom or considering one, we would encourage you to download the guide and go through it, but we also thought we would produce a bit of a guide to the guide.

Considering Game Mechanics

Obviously choosing an underlying game mechanic is a critical first step, but in the guide there are some interesting things for developers to consider that may help them view where their mechanic fits in a broader range of games.

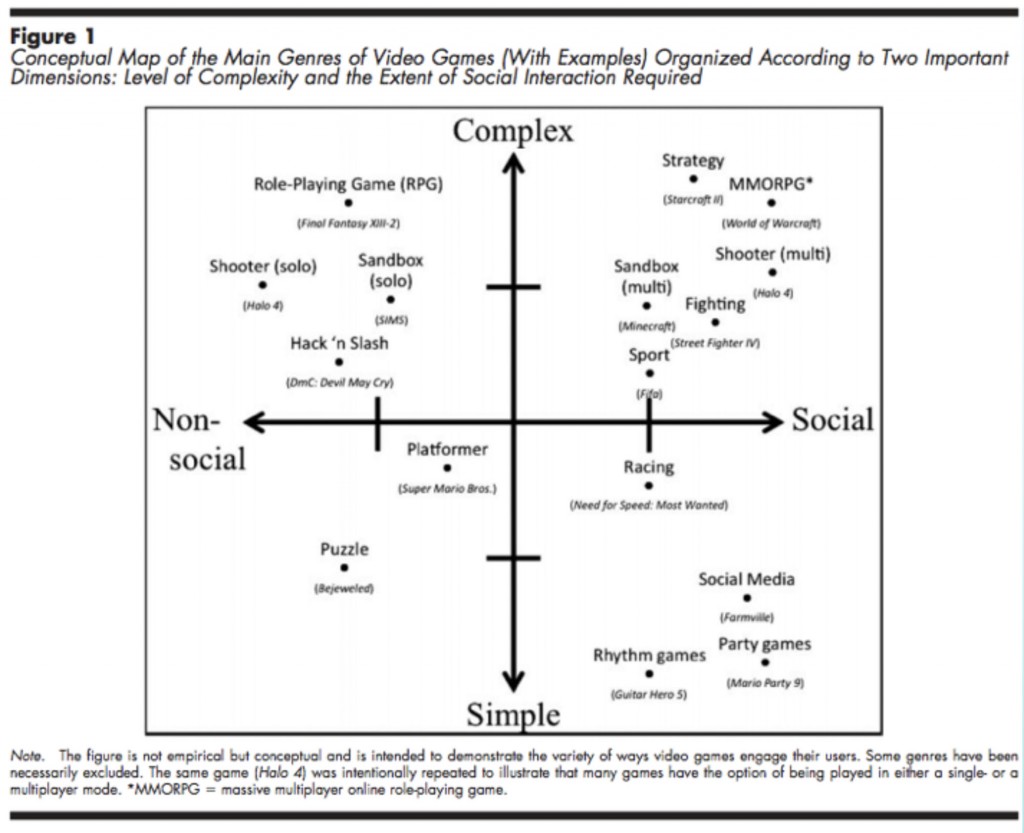

For instance, the guide includes this handy graphic:

That helps a designer consider how social and how inherently complex their type of game may turn out to be.

An additional insight that might help is to consider how the game would actually fit into a school.

Here Shapiro has some real food for thought for developers about whether their game is a short- or long-form product:

Short-form games tend to resemble the kinds of casual smartphone games that even adults tend to fiddle with during idle time. Wuzzit Trouble, for example, the game Keith Devlin created in order to allow students to actively experience number partitions, can occupy a player for hours, or it can be played for 10-15 minutes. Played in small doses, short-form games can serve as great interactive examples, reinforcing and supplementing a teacher-driven curriculum. Short-form games tend to work best for learning when they’re focused on a specific skill set or concept. Think of them like brief simulations.

Long-form games tend to be more open-ended and intricate. These games often start simply and expand over time, so they can easily form the backbone of an entire curriculum. The Cooney Center reports that recent research “points to the significant engagement factor produced by longform learning games.” The coherent unification around both short-term and long-term goals leads increased motivation and ongoing commitment to class projects. In addition, long-form games tend to foster skills like “critical thinking, problem solving, collaboration, creativity, and communication.”

Data on Screentime and Impact

The guide also brings together some recent research and surveys that help build a compelling case for games in the classroom – and could also be used to build a compelling case for supporting the development of learning games.

Some key Data

- 30% of the teachers said the games are equally beneficial for all students.

- 65% of teachers note that lower-performing students show increased engagement with content, versus only 3% who show a decrease.

- 62% of online gamers hold a favorable view of people from different cultures compared to 50% of non-gamers.

- Students who had games as part of their schooling would have increased scores by 12%.

The guide, although written for teachers, serves as a road map to understanding the needs of one of the most significant audiences for a learning game, so it’s worth reading the whole thing if you plan on taking your game into the classroom.

On Wednesday we will report on what tips the guide has for developers hoping to have more teachers discover and use their game.