Learning games have yet to crack the code to making a popular card game.

It may be a digital download world for many, but more and more 21st-century gamers are breaking out decks of cards to play hybrid digital card games.

With roughly 30 million registered users in its first year of release, Blizzard Entertainment’s Collectible Card Game (CCG) Hearthstone has attracted more than twice as many players its aesthetic forbearer and longstanding revenue juggernaut World of Warcraft, which at its 2010 peak boasted about 12 million users.

Turns out people really love colorful cards with goblins, demons and gnomes and spells, and smashing them into each other on a beautifully animated, interactive digital game board online for free.

Competing publisher Bethesda Softworks, makers of popular commercial titles like the Elder Scrolls and Fallout series, announced last month at E3 2015 they’re also jumping into the CCG fray with an Elder Scrolls-inspired card game at the end of the year, joining Hearthstone and long-time CCG stalwarts Magic: The Gathering and Pokémon in a global $4.1 billion market.

The collectible card game is also becoming a major player in the burgeoning realm of “eSports,” a concept even analysts on Wall Street are starting to scrutinize. But educational developers seem to have little, if any, role in the booming digital card game business.

Though there’s clearly a commercial consumer demand for modern trading and collectible card games, there’s little evidence the format and game mechanics lend themselves to educational learning. How does one market something like and a classroom CCG to educator, and does it even make sense to try?

If you’re an educational games developer looking for a new consumer market, there are some factors that make it look like a strong possibility.

Learning games revenue could reach $2.5 billion dollars by 2018, but some industry leaders are looking to rely less on government grants and deals with school districts and start relying exclusively on the consumer market, which spends nearly five times more on games than K -12 organizations.

In a recent interview with VentureBeat, Filament Games co-founder Dan White said making a quick profit in educational games is “frankly, impossible,” and expressed his desire to wean his company off the grant cycle completely, saying, “it’s important that we start to do products that are extremely market driven.”

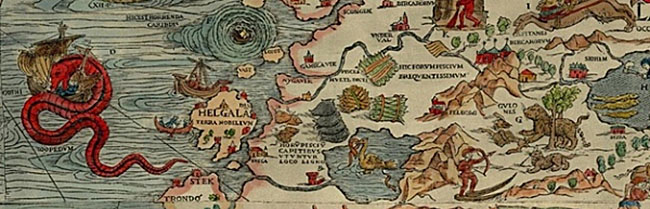

Here Be Dragons

Learning card games, pictured left.

There’s little precedent for a CCG-style educational tool that doesn’t boil down to a simple flash card app or skill-and-drill exercise. So the educational card game is a bit mythical. Not to say there aren’t educational tools that use trading cards as inspiration, but they tend to be designed as supplements for teachers to shake up homework assignments and study habits.

For example, ReadWriteThink, a free interactive literacy resource, has a flash-based generator that allows a student to create a digital trading card from an assignment. Although students can upload a photo or insert interesting facts, descriptions or narratives the generator feels much more like a clever study tool rather than a component of a greater educational concept based around competitive collecting or trading.

It’s difficult to find one that does, and educators have been looking, attracted by the power of other card games.

Researchers at Cambridge were waving their arms at the educational community as far back as 2002, when they noted in Science Magazine that 8-year-olds can memorize and identify the looks, groups and stats of the nearly every creature in the 150-card pool of the Pokémon, but when the subject changes to real life flora and fauna, like oak trees and badgers, performance drops dramatically.

NASA was so impressed by Pokémon’s learning potential, they joined forces to make a special card based on DNA research.

But there’s been little concrete consensus where the educational community can go from here to translate that Pokémon passion into something meaningful in schools.

A 2009 joint study out of Chung Yuan Christian University and MingDao University, both in Taiwan, took pointers from extremely popular CCG games like Magic: The Gathering and Yu-Gi-Oh! to design a card game specifically meant to motivate students in the classroom.

The cards and user interface are quite skeletal, but depict albino tigers, elegant ninjas and mythological creatures such as griffins and chimeras, all bearing individual stats that a player uses to fight it out against a distant opponent on a digital tabletop.

The designers chose to reward students with credits for smart play rather than simply track their win/loss records. In some cases, a player can actually earn more credits during a loss than a win, which separates the experiment from nearly every traditional CCG.

Of course, the entire concept of education through card collecting and battles revolves around competition, which is far from accepted by educators and thinkers as appropriate in the classroom. But these researchers hope the draw of earning a rare or powerful card will help motivate students who are intimidated or turned-off by competition.

“You will get new cards from time to time if you have done a good job doing homework, you have a good performance in an exam or any other selected activities,” explained researcher Maiga Chang during a video demonstration of the card game mechanics.

The Design Challenge

And therein lies the problem. Student learning in a relevant subject like history, reading or math — besides the general arithmetic and strategy needed to play a card game — is tied to performance outside the core gameplay rather than integrated within.

Teachers would need to develop a system to decide which learning activities rewarded what type of card, making it difficult to discern the difference between giving a student who turns in her homework early to earn a coveted card, and just handing out stickers or badges. There’s also little to no data demonstrating what direct impact the game has on how well students learn.

In a 2012 Harvard study of trading card games’ educational potential, researchers highlighted how little we know about such a popular genre of games, saying “the lack of thought pieces or experimental studies with CCGs is surprising.”

But what little research we do have indicates card games, in general, can be effective learning tools. In the Harvard study, 365 players, aged 18 to 59, said they were drawn to the deck-building aspect of CCGs, and about half felt motivated to “learn from their mistakes and use this as a strength in the future.”

Researcher concluded that “if CCGs are to be used as learning tools, educators should leverage the motivational power of deck building and social aspect of the game at the same time taking advantage of the fact that CCGs are built on analytical processes, and they require assimilation and interpretation of symbols.”

That may sound obtuse, but consider that tens of millions of commercial card gamers do it online every day, over the course of thousands of gameplay decisions based on the stats of hundreds of cards, all with the constant feedback of dedicated gamer communities and forums.

There are a horde of CCGs on mobile platforms in particular, many of them free-to-play, with the option to use real money to buy in-game currency, which players can use to buy digital card packs. Many of these games have a notable Japanese animé feel, and all require players to use surprisingly higher level math, strategy and categorizational skills in order to defeat either computer or human opponents and earn the rush of opening digital card packs to go along with their card collection and deck-building theme.

What’s lacking is a popular and successful merger of a physical educational card game with an easily accessible, fun digital platform. The developer who cracks that code could find themselves tapping into a new and profitable educational market.