If Evidence-Centered Design (ECD) was about making games that are built to assess student learning, MIT’s new idea of Balanced Design may be the more game designer-friendly way of bridging the gap between the game and assessment camps.

The MIT Scheller Teacher Education Program and Education Arcade have teamed up to produce a new 30-page guide they hope will be the next step in creating more engaging and more successful learning games.

“The aim of the guide is not to impose a new game development method—but rather to present a learning design approach to be integrated with current best practices in game design,” the team wrote. “The emphasis of this framework is not directly for building assessments into games but rather helping game designers to better align the learning goals with game mechanics to produce more deeply engaging and effective learning game experiences.”

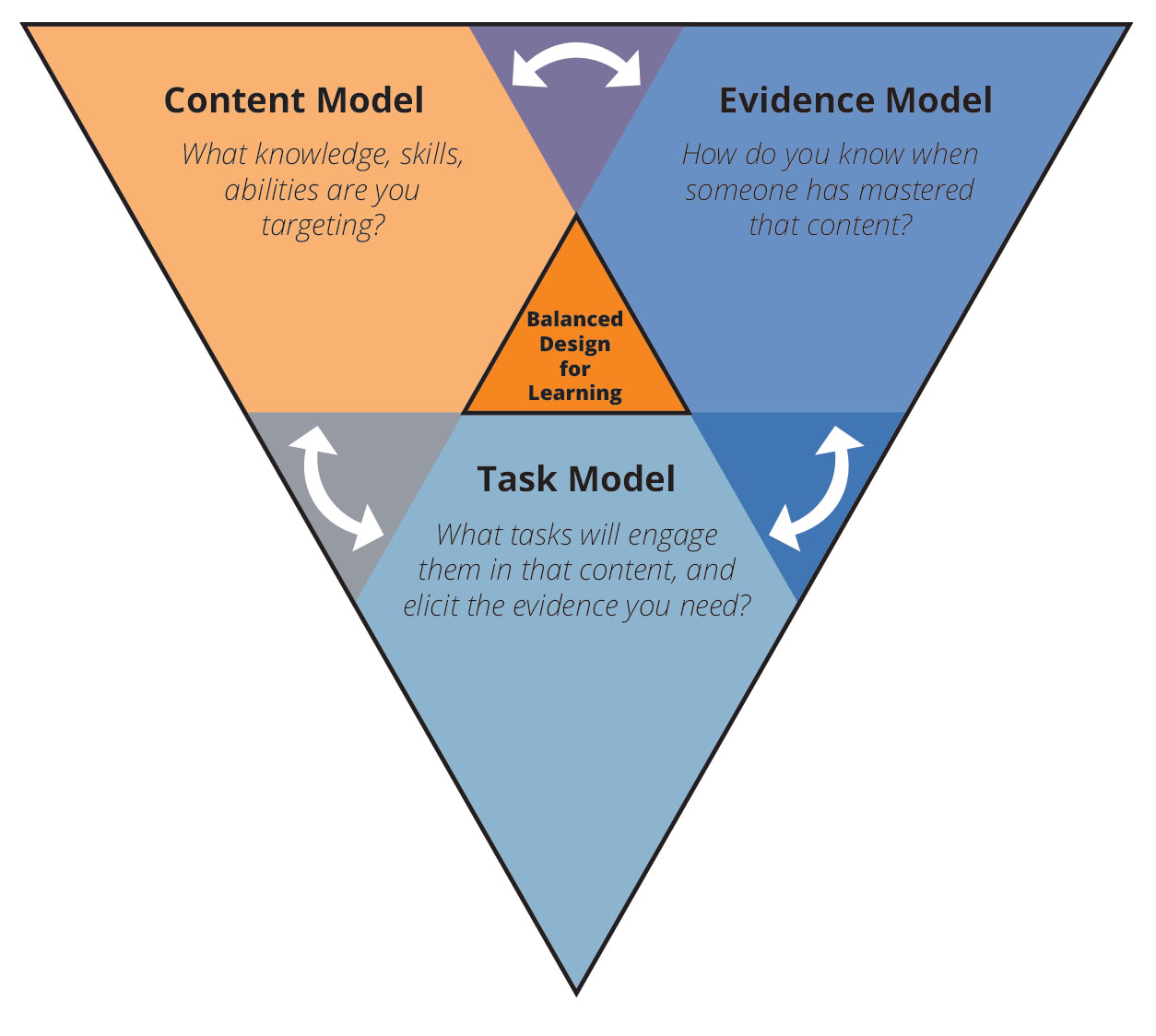

The model they have proposed, dubbed “Balance Design,” seeks to break down the more involved and complex ECD approach into three core concepts, or what they call models: The Content Model, the Task Model and the Evidence Model.

The break down essentially like this:

The Content Model

This element of the design outlines what the game aims to teach and delineates what levels of proficiency learners should achieve. The team calls this, “the heart of a learning game, because it deeply defines the content—without which, one cannot be certain as to what the game is actually addressing.”

The Task Model

This part of the design details the gameplay and clearly maps out the quests or challenges a play must tackle within the game. It also creates a list of data points produced in the game.

The Evidence Model

The final model outlines how the data produced by the game is interpreted to gauge a player’s understanding of the skills or knowledge the game aims to instill. It also outlines how the game will change based on the outcome of that measurement.

It’s obviously a lot more involved than these three steps, but the idea in this shift seems to be to create a set of loose rules around game development that allow interested parties – teachers, parents, etc. – to be able to understand how the player is doing without having a rigid set of rules around how the game is built.

As a field, we have built some impressive learning games. But designing these games on a more coherent framework, and documenting that for the learners and educators who will use your game represents not just a promising step forward, but evidence of true ‘alignment’ of learning, task and evidence data, that largely has not been present in the field of learning games to this point.

— MIT authors

It’s the second time this summer we have had a major outlet connected with the assessment side of learning games outline a subtle shift in their focus. Last month we talked with GlassLab that said they were looking more at a data structure that could produce reports to teachers rather than a formal assessment structure.

Mat Frenz at GlassLab talked about how their assessment work has taught them that the best way to work with game designers is not to dictate a formal assessment regime, but rather to build a framework that allows developers to improve the performance of their own games to deliver better data.

“When I think about technology and how it grows, I think about evolution. It’s really difficult to leap-frog those evolutions and I think that was what we were trying to do with our initial approach to assessment. We were trying go 7-8-10 years into the future, without building that year 1, 2, 3 evolution,” he said.

“The shift from assessment to data structures I don’t think is a pivot. I don’t think it’s a turning away from our initial goal. I think we are just getting smarter.”

MIT’s proposal seems to represent another effort to find a middle ground between the formal assessment work that has fueled many academic learning game developers and the more informal feedback loops that have been built into consumer learning games.